This paper examines the Columbia STS-107 space shuttle accident with a human factors perspective. The Columbia Accident Investigation Board’s (CAIB) conclusion about the physical cause of the accident was reinforced; however, further accident analysis was conducted using the Human Factors Investigation Tool (HFIT). As outlined, the Columbia STS-107 vehicle disintegrated upon reentry into Earth’s atmosphere because of a breach in the left wing of the shuttle due to a foam impact incident that happened during life-off. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), coupled with other outside agencies and teams, refused to investigate into the initial impact event. Because of this, as well as other contributing factors, the mission members were ignorant of the danger that the Columbia shuttle was in when reentering into Earth’s atmosphere. Other factors outlined in this paper that contributed to the accident include operational, technical and various human errors. Through this accident investigation analysis, it is hoped that safety and technological stability, as well as a healthy and productive organizational environment are established in the aerospace industry.

Keywords: Columbia STS-107, Accident, HFIT

Columbia STS-107 Accident Analysis

Although there are clear benefits to involving human factors professionals in the workings of the aerospace industry, there has been a large lack of application and human or user centered perspectives being utilized. This can especially be seen throughout the investigation conducted on the Columbia STS-107 space shuttle accident. Considering the severity of this disaster, resulting in the complete break-up of the shuttle upon reentry that killed all seven crewmembers, an investigation board was immediately created. Despite the clarity, determinism and contributions of the investigation board, there was a clear lack of human factors perspectives throughout the analysis. Not only does a secondary examination of this incident need to be conducted, but human factors and ergonomic analysis tools need to be implemented and utilized to prevent future errors and incidents.

Human Factors in the Aerospace Industry

The field of human factors is a scientific discipline that focuses on the capabilities, limitations, errors and interactions of machines, tools, systems, tasks, environments and people. Human factor professionals have been increasingly concerned with the evaluation, design and interactions of human-machine systems, as well as the ever-evolving capabilities, limitations and errors of both the human and machine. As outlined by Merlin, Bendrick & Holland (2014), this profession applies theory, principles, data and other methods to design in order to optimize human well-being and overall system performance (P. xii). Covering topics that range from ergonomics, human and machine error, product design and workplace safety, the field of human factors have greatly contributed to many industries and organizations. When applied to aerospace operations, human factors professionals use their knowledge to identify, investigate and prevent accidents, incidents and errors with the goal of optimizing the workings of people and machine systems to ensure safety and improve overall performance.

Many of today’s modern technological innovations have emerged from the aerospace industry with the help of scientists, researchers, designers, engineers and human factors professionals. With its emphasis on human-centered or user-centered design, human factors professionals help ensure that the many aspects of the aerospace industry suit the people, tasks and environments involved in both safe, effective and efficient ways. As outlined by Ludvigsen, Mouloua & Hancock (2015) some of the human factors aerospace research includes studies on cockpit interfaces, pilot capabilities and limitations, aviation systems, team and crew interactions, the effects of the weather and environment, and much more (P. 21). Due to the new boundaries often breached during the development, testing, and deployment of these systems, many amazing feats have been accomplished, as well as mishaps involving human physiology and psychology, organizational issues and vehicle design flaws (Ludvigsen, Mouloua & Hancock, 2015, P. 20). With this, a large part of the human factors field in the aerospace industry has been to maintain safety, efficiency and effectiveness through the identification and prevention of human and technological errors.

Aerospace Accident Investigation

When it comes to spaceflight and the overall aerospace industry, incidents, accidents, errors and down-right disasters are no strangers. Although accidents involving people, aircraft and spacecraft were once generally attributed to human error, the significance of taking a human factors perspective in these mishaps and considering other implicating factors have been increasingly considered. Not only do these incidents involve a wide range of human factors issues, but also layers of operational, situational and organizational factors (Merlin, Bendrick & Holland, 2014, P. 189). Aspects including personal bias, poor communication, technological and electronic malfunctions, management and resource issues, as well as inadequate supervision and decision making have all been contributing threats to the aerospace industry. Throughout the entirety of the shuttle program and our pioneer into outer space, there have been noted design, physiological and organizational flaws that have heavily contributed to aerospace accidents. This can be seen time and time again in accidents such as the Challenger disaster of 1986 and the Columbia accident of 2003.

Columbia Accident of 2003

One of the National Aeronautics and Space Administrations (NASA) most known accomplishments has been the space shuttle program. The space shuttle Columbia was the first of NASA’s orbiter fleets with liftoff in 1981. Lasting till year 2003, the shuttle’s missions included the construction of the International Space Station (ISS), the first manned missions into space, the first satellite recovery and more. Not only did Columbia successfully prove the operational concept of a winged and reusable spaceship, but it also holds the position for being the first spacelab mission totally dedicated to human medical research (Dunbar & Ryba, 2008). With these amazing accomplishments came an even grander end when the Columbia STS-107 flight disintegrated upon reentry into Earth’s atmosphere on the first of February in 2003.

The Columbia STS-107 mission, being the last one of the program and Columbia’s 113th space shuttle flight, involved seventy-seven flight control room operators with seven astronaut crewmembers. The seven crewmembers spent sixteen days in space on the ISS, completing a wide variety of experiments and tasks. At the mission’s conclusion, Columbia STS-107 made its fatal decent into Earth’s atmosphere and eventually disintegrated over Texas, killing all seven crewmembers, due to a debris strike that resulted in an exposure in the shuttle’s heat shield.

An investigation board was immediately formed after the accident, creating an in-depth report of the ensuing factors that contributed to the Columbia disaster. The Columbia Accident Investigation Board (CAIB), which was drafted jointly by researchers and academics, handed in its conclusions at the end of August, 2003 (Dien and Llory, 2004, P. 4). The investigation conducted by this board included an organizational analysis, a look at the human and management errors, as well as failures in the shuttle’s technical systems and overall design. As best outlined by Dien and Llory (2004), the fundamental analysis aspects within the structure of the enquiry and the investigation report includes the history of the shuttle program, the various interactions and organizational networks surrounding the incident, and the decision-making processes that led to the accident. Despite this investigation and their understanding of all contributing factors, human factors and ergonomic investigation tools need to be utilized to guarantee comprehension and prevention of the influencing errors that occurred during this incident.

A Tool for Investigation

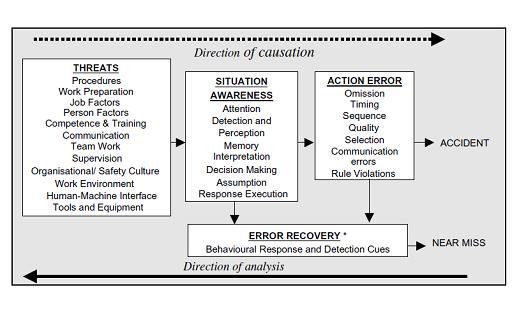

The investigation method used in this study to reexamine the Columbia STS-107 accident is the Human Factors Investigation Tool (HFIT). This tool, as best outlined by Gordon, Flin and Mearns (2005), analyses four types of human factors information including (a) the action errors occurring immediately prior to the incident, (b) error recovery mechanisms, in the case of near misses, (c) the thought processes and situational awareness that led to the action errors and (d) the underlying threats and causes. This method, providing a systematic interview structure for exploring aspects of an accident or incident, investigates twenty-eight types of human and organizational factors within these four human factors components. Researchers Flin, Fioratou, Ferk, Trotter and Cook (2013) outline the various components and factors utilized within this tool, as well as the direction of investigation analysis, in Figure 1.

(Flin, Fioratou, Ferk, Trotter & Cook, 2013).

The model of the HFIT depicted in Figure 1 illustrates the four components which make up the investigation tool, being threats, situation awareness, action error and error recovery. Within these four categories are the various elements, allowing for a true, in-depth human factors analysis of the accident or incident. This tool will be used to further investigate and reexamine the Columbia STS-107 accident in all its entirety.

Human Factors Investigation of the 2003 Columbia Accident

With the use of the CAIB material, a human factors investigation needs to be done regarding the 2003 Columbia STS-107 accident. An HFIT analysis of the disaster will be conducted with the use of the CAIB’s detailed report through the following four-step process: 1) Identify the action errors, 2) Identify the error recovery mechanisms, 3) Identify the various elements of information processing sequences and situational awareness aspects that failed, and 4) Identify the threats that contributed to the accident.

Actions Error

The actions error concerning this accident were quite shocking and included omission, quality and communication errors. Although there were technically no rule violations, there were still some major issues regarding evaluation techniques and other protocols.

In short, there was a clear and complete disregard for the potential damage that the foam impact caused. After the initial analysis of the foam impact, mission control notified the commander on ISS with a statement reinforcing that there was no concerning damage. This communication error led to Columbia’s crewmembers being completely unaware that there was an issue with the shuttle until it was too late. After this transmission, several attempts were made by various NASA personnel to further investigate the debris impact area with imaging techniques, but all three attempts were either denied or ignored.

It is also important to note the lack of addressing the technological and design quality issues within the shuttle. Specifically, there were many concerns raised about debris foam anomalies, being that the Columbia STS-107 flight was the seventh significant foam loss incident recorded which resulted in the shuttle’s disintegration; however, none of these impacts or anomalies were addressed. Instead, they were deemed ‘normal’ and not dangerous to flight operations. This resulted in NASA’s debris impact requirements not being met on a single mission, NASA failing to adequately perform trend analysis on foam losses, and NASA’s failure to harden the orbiters shell against debris foam impacts. Another contributing factor to the Columbia accident includes mission control and the NASA team ignoring broken and failing sensors, as well as other various subpar equipment on the shuttles such as weld defects and foam properties.

Despite the many voiced concerns, no risk assessments or further investigations were conducted to assess the probability and seriousness of the Columbia debris impact and shuttle quality. Instead of addressing these various issues, NASA supervisors and mission management proceeded with a false indication that mission success had a high probability despite the known damage, ultimately allowing Columbia to reenter into Earth’s atmosphere with an existing breach in the left wing’s heat shield. These task omissions, communication and quality issues made by qualified NASA personnel all contributed to the Columbia STS-107 accident that not only altered the course of accident investigation, but the entire aerospace industry as well.

Error Recovery

Despite the attempts at error recovery, none of the behavioral responses and detection cues were successful. After the debris foam impact and the initial analysis, the NASA team at mission control sent a transmission to the Columbia crewmembers notifying them of the incident; however, it was reinforced that there was no concerning damage. With this, none of the crewmembers on the shuttle were cognizant of the damage to be able to recover from it. Although NASA’s mission control and the various personnel associated with the space shuttle program knew about the damage to the left wing, there was little-to-nothing done to mend it. In fact, as noted earlier, the investigation attempts that were made by concerned personnel were refused or ignored.

Upon re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere when the crewmembers and mission control began losing control of the shuttle, a brief attempt was made to compensate for the damaged wing but the high temperatures and pressure were too overwhelming. A few seconds later, communication was lost between the crewmembers and NASA headquarters, and the Columbia STS-107 shuttle began disintegrating. With nothing more to do, the clean-up and investigation began.

Situation Awareness

There were a few noted problems regarding situation awareness that needs to be addressed, including issues with decision making, assumption and response execution.

The initiating event, being the foam impact with the left wing of the shuttle, preceded the accident by more than two weeks. As outlined by Dien and Llory (2004), the impact of the insulting foam debris had been identified by the second day of the Columbia mission, as well as the substantial size of the debris and the relative speed of the strike on the leading edge of the wing had both been correctly assessed by an informal debris assessment team (P. 6). This team concluded that it was crucial and extremely urgent that they obtain high-resolution images of the impact area on the wing. This would give them the ability to better assess the potential risks at the time of re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere; however, requests for these images were denied. It was also transmitted to the crewmembers that there was no concerning damage to the shuttle’s wing and that the mission should continue as normal, making it unclear whether the crewmembers were aware that the shuttle was breaking apart around them upon reentry into Earth’s atmosphere.

Because mission control refused the damage imaging and further investigation into the impact event, they made themselves and the crewmembers onboard the shuttle ignorant to the severity of the damage that the foam loss caused to the left wing. Coupled with the assumption that the space shuttle program is outdated which led to the lack of addressing system failures and malfunctions, the mission members did not notice anything seriously troubling until about ten minutes after entry interface. This means that the shuttle was already too far into Earth’s atmosphere to change course, address the damage or attempt to fix the situation once aware. Thus, the disintegration of the Columbia STS-107 space shuttle.

Another interesting situational issue that the CAIB noted in their accident report was the fact that NASA mission control was initially unaware of the disintegration of the shuttle due to communication loss until one of the mission control team members received a telephone call notifying them of live television coverage of the break-up (Barry et Al., 2003). Once aware of the situation, the mission members used military and civilian camera documentation to record and examine the accident.

Threats

Before the Columbia STS-107 space shuttle accident occurred, there were several noted threats to the mission that were either disregarded or overlooked. The known threats include procedural issues, work preparation, job factors, organizational and safety culture, communication and supervision, work environment, as well as tools and equipment.

Within the NASA organization, there were many operating threats and work culture issues that need to be addressed. Not only were there problems with scarce resources and funding, workforce cuts, management and leadership changes, increased privatization, and inadequate inspection, evaluation and analysis techniques, but there were also noted production pressures such as schedules and deadlines, breakdowns in communication such as withholding information and a lack of in-depth or clear debates, excessive formalism such as the emphasis on the chain of command and procedurization, and marked biases in the decision-making processes. A lot of these procedural, preparation, communication, organizational and safety issues can be attributed to the assumptions made about the NASA shuttle program, specifically the belief that the shuttle’s systems were outdated and the program was on its way to retirement. This assumption led NASA personnel to ignore these various workplace issues, as well as the defective and failing systems despite their continued spaceflight missions.

These workplace factors led to issues with the shuttle itself, including a lack in understanding of the External Tanks foam properties and behaviors, as well as noted weld defects, cracks and leaks which all had to be addressed before lift-off. In fact, the CAIB enquiry revealed that the space shuttles before Columbia STS-107 all had insulating foam material detach from the shuttle (Barry et Al., 2003). Despite the regular detachment and impact of this foam occurring on every single space shuttle flight, the issue was never adequately addressed. This is also the case with failing and broken sensors within the shuttle, which were all neglected and ignored. In fact, as Dien and Llory (2004) outline, the historical examination of the reactions of NASA’s managers and experts show that there is a progressive decline in appreciation of the potential risks regarding the shuttle (P. 6-7). On top of this, other threats included environmental and weather factors such as thermal and vacuum effects, radiation, the effects of microgravity, as well as vibrations and payload.

In short, the NASA culture began accepting more risks while their safety program was largely silent and ineffective. This risk acceptance, as well as the environmental factors, clear neglect and disregard for the shuttle’s technological state, the inadequate oversight and the noted requirement confusion, all heavily contributed to the Columbia STS-107 shuttle accident.

Discussion

As noted earlier, Columbia STS-107’s launch was the seventh known bipod ramp foam loss event. Due to this loss of foam, a breach in the Thermal Protection System on the leading edge of the left wing was created. This foam impact left the wing with a hole that allowed high temperatures and gases to penetrate the shuttle’s system, leading to the loss of control of the shuttle and its disintegration upon reentry into Earth’s atmosphere. Through using a combination of tests and analyses, the CAIB concluded that the observed foam loss and its impact with the orbiters left wing during liftoff was the direct, physical cause of the accident (Barry et. Al., 2003). It should also be noted that although the CAIB acknowledged workplace, organizational and human factors that contributed to the incident, there was no blame placed on NASA personnel or these various factors for the Columbia STS-107 accident.

The results from the HFIT analysis reinforce the conclusion made by the CAIB that the physical cause of the accident was the foam debris impact; however, there were several attributing and concerning factors found that the CAIB did not explicitly address. This included organizational and workplace issues, as well as technological and electronic shortcomings, a clear lack of a safety culture and extremely poor decision-making made by NASA personnel.

Conclusion

The ensuing HFIT analysis outlines the 2003 Columbia STS-107 space shuttle accident. This disaster, as it states above, is riddled with operational, technological and human errors. Since this horrific event, there have been several steps made to ensure the safety and future of spaceflight. As Dien and Llory (2004) conclude best, the accident of the Columbia space shuttle and the ensuing reports provide us with an opportunity for in-depth examinations of incidents, knowledge about and analysis of industrial accidents and failure, as well as the models of thought relating to an event and its dynamics, normal and pathological organizational phenomena, local conditions and global organizational causes of accidents, and the processes of causality (P. 3). Despite these benefits, the most important thing to take away from the Columbia STS-107 accident is that it is better to take the time to insure safety than to be sorry you didn’t.

References

Barry, J., Deal, D., Hess, K., Logsdon, J., Ride, S., Turcotte, S., … Hallock, J. (2003). Columbia Accident Investigation Board. Columbia Accident Investigation Board (Vol. 1, pp. 1–243). Government Printing Office.

Dien, Y., & Llory, M. (2004). Effects of the Columbia Space Shuttle Accident on High-Risk Industries or can we Learn Lessons from Other Industries. Hazards, 1–15.

Dunbar, B., & Ryba, J. (2008). Space Shuttle Columbia. Retrieved from https://www.nasa.gov/centers/kennedy/shuttleoperations/orbiters/orbiterscol.html.

Flin, R., Fioratou, E., Frerk, C., Trotter, C., & Cook, T. M. (2013). Human factors in the development of complications of airway management: preliminary evaluation of an interview tool. Anaesthesia, 68(8), 817–825. doi: 10.1111/anae.12253

Gordon, R., Flin, R., & Mearns, K. (2005). Designing and evaluating a human factors investigation tool (HFIT) for accident analysis. Safety Science, 43(3), 147–171. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2005.02.002

Ludvigsen, J., Mouloua, M., & Hancock, P. A. (2015). Human Factors/Ergonomics Contributions to Aerospace Systems, 1980–2012. Ergonomics in Design: The Quarterly of Human Factors Applications, 23(4), 20–22. doi: 10.1177/1064804615572627

Merlin, P. W., Bendrick, G. A., & Holland, D. A. (2014). Breaking the mishap chain: human factors lessons learned from aerospace accidents and incidents in research, flight test, and development. Place of publication not identified: Books Express Publishing.

Originally created by Samantha Colangelo to fulfill requirements for Embry Riddle Aeronautical University’s Master of Science program in Human Factors. December, 2019.