This paper takes a qualitative approach to investigate the use of Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCI) for space operations. A brief literature review was conducted outlining the outer-space environment and human capabilities in space, different types of affective neural devices and their use for space operations, and various evaluation methods for assessing performance. Specifically, it is described how BCIs can greatly assist in communication, machine operation, and human-monitoring endeavors during missions in space. This research concludes that the application of these devices, specifically non-invasive BCIs, would lead to an increase in performance throughout this discipline. System performance assessments and evaluation measures were also suggested to ensure this improvement, including direct system feedback, the implementation of rejection criteria, and using a supervisory artificial intelligence. In conclusion, further research and testing are needed of the inter-workings and limitations of this BCI technology, the connection between humans and machines in space, as well as the effects that non-invasive and invasive neural networks have on the human brain under the conditions of space.

Keywords: Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCI), Non-Invasive, Invasive, Partially Invasive

Brain-Computer Interfaces for Space Operations

An increasingly attractive application for Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCI) is the aerospace industry for space operations. With the development of various technological designs, there are several useful applications of these devices for space. The implementation of BCI devices for long-duration spaceflight operations, with a practical and human-centric design, is believed to significantly increase communication abilities and assist in controlling machines operating in the harsh alien environment. To investigate these claims and applications, there first needs to be an understanding of what BCI technologies are, as well as the environmental conditions in space and various limitations experienced by astronauts that create the need for these interfaces.

BCI Technology

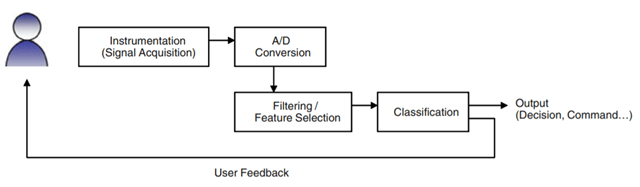

A Brain-Computer Interface (BCI), as broadly defined by Moxon and Foffani (2015), is an artificial process that allows the brain to exchange information directly with an external device through the translation of their intended actions or mental tasks. Being put forward around the 1970s as a direct interface between brain and machine, this technology is a more natural way to augment human capabilities by providing new interaction links with the outside world (Negueruela, Broschart, Menon, and Millan, 2011). As thoroughly outlined by Negueruela, Broschart, Menon, and Millan (2011) below in Figure 1, the first step of implementing BCI technology is acquiring and monitoring the correct brain signals with the correct instrumentation. As also shown below in Figure 1, these signals are acquired, conditioned, and converted to a digital format for filtering and further processing where they can then be interpreted and classified against a carefully designed application-dependent protocol that specifies the choice of parameters and mental tasks to be performance (Negueruela, Broschart, Menon & Millan, 2011).

(Negueruela, Broschart, Menon, and Millan, 2011)

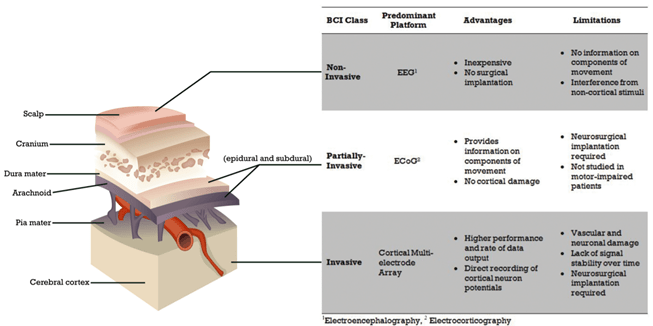

With this, there are also a variety of methods to monitor brain activity for BCI systems, including both invasive and non-invasive techniques. As described by Negueruela, Broschart, Menon, and Millan (2011), most non-invasive BCI systems use electroencephalogram (EEG) signals where electrical brain activities are recorded directly from the surface of the operator’s scalp. Other signals that could be used in a BCI system, as listed by Negueruela, Broschart, Menon, and Millan (2011), include magnetic and metabolic activity with recording devices such as the magnetoencephalography (MEG), functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), Positron Emission Tomography (PET) and optical imaging. Despite the simplicity of these methods, they do not provide detailed information on the activity of small brain areas and is characterized by noisy measurements and small amplitudes in the range of a few micro-volts (Negueruela, Broschart, Menon, and Millan, 2011). Invasive BCI systems, as outlined further by Negueruela, Broschart, Menon, and Millan (2011), measures the activity of single neurons from microelectrodes directly implanted in the brain. Although these techniques can provide signals that are less noisy than EEG signals and with higher spatial resolution, they require repeated surgical operations and treatments due to the possible formation of lasting scar tissue that impacts the electrical signal’s strength (Negueruela, Broschart, Menon & Millan, 2011). Partially invasive (or semi-invasive) BCIs reduce the risk of surgery infection and the formation of scar tissue and is suggested to be more powerful and stable than non-invasive systems; however, the signal strength and recognition is weaker than in the case of invasive BCIs and is still susceptible to noise (Negueruela, Broschart, Menon & Millan, 2011). These three classes of BCI systems, as well as their anatomical locations, advantages, and limitations, are outlined below in Figure 2.

(Kotchetkov et al, 2010)

Although the types of BCI devices are diverse, there are currently only a few applications and industries utilizing them. As outlined by Gemignani, Gheysens, and Summerer (2015), advances in this field have mostly been driven by the need for new medical applications for assistive care and communication solutions. There have also been considerations of military and aerospace applications for moving robotics, vehicles, and controlling weaponry (Negueruela, Broschart, Menon & Millan, 2011). Despite these various devices and applications, utilizing this technology in space for productive and efficient operations is a progressive and seemingly necessary step towards frequent and safe human space exploration. Although, the various hazards, applications, and influencing factors need to be explored further.

Space Hazards and Uses of BCIs

Along with the increased activity and diverse operations being conducted in space, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) has identified several hazards for human exploration, which include space radiation, isolation, distance from Earth, micro and reduced gravity, and the generally hostile environment (NASA, 2018). Not only does this result in safety concerns for space travel, but as outlined by Gemignani, Gheysens, and Summerer (2015), these issues also have direct impacts on mission factors including the spacecraft design, the chosen activities and operations, astronaut selection and preparation, and the required supporting and enabling technologies. To mitigate these issues, it was proposed by Clynes & Kline (1960) that altering a human’s bodily functions to meet the requirements of extraterrestrial environments would be more logical than providing an earthly environment in space. Since this claim, several researchers have reinforced this concept that enhancement is not just an effective countermeasure but is a mandatory necessity for human development in space.

The main reason for human enhancement in space, as outlined by Szocik and Braddock (2019), is the fact that currently applied countermeasures to these health issues and concerns are not sufficient (i.e., diet, exercise, pharmaceuticals, and anti-radiation shielding). Other reasons for this enhancement include increasing the quality of life and wellbeing, providing improved medical protection and human performance, and adapting to the space environment (Szocik & Braddock, 2019). Any enhancement applied to astronauts, as further defined by Szocik and Braddock (2019), should be aimed at increasing resistance and adaptivity to hazardous space factors, and will be a new type of therapeutic intervention where human functions and capacities are positively modulated. Although seemingly controversial, the types of enhancement that are considered include genetic engineering, the development of a protective exoskeleton, robotics and nanotechnology, pharmaceutical interventions, and programs of cognitive and neuronal enhancements (Szocik & Braddock, 2019). This not only encompasses several types of human-robot interactions, but also the utilization of BCIs.

By opening-up new possibilities in human–robot interaction, the use of BCI technology and direct mental teleoperation in the aerospace application would greatly benefit astronauts. Specific space applications include both critical and noncritical functions, with BCI technologies benefiting several mission operations ranging from robotics, communication, and even monitoring astronauts’ cognitive state. Through the BCIs ability to bypass direct interaction with the environment, astronauts can mentally send commands to external auxiliary artificial systems when in a limited workspace and harsh environment without any output or latency delay (Negueruela, Broschart, Menon & Millan, 2011). By bypassing the need of any manual interface (i.e., joysticks, buttons, and other physical controls), commands can be sent without delay or distortion which also makes these systems extremely useful for the launch and landing of spacecrafts, exploration endeavors, performance improvement, and detecting emergency situations (Negueruela, Broschart, Menon & Millan, 2011). This additional and direct communication channel would not only allow for the use of an astronaut’s electrical brain activity to directly control external artificial systems, but it would also reduce associated mission costs through the increase in operational efficiency that results from one single astronaut having the capability to multitask and perform several operations (Negueruela, Broschart, Menon & Millan, 2011).

BCIs could also be an efficient interface to have full control of robotic systems and semiautomatic devices of the spaceship through a single wearable interface, making them an essential element in the application of space operations (Negueruela, Broschart, Menon & Millan, 2011). In fact, researcher Pecora et al (2016) proposed that this technology be used for robotic uses outside the spacecrafts, completing dangerous tasks and limiting the astronaut’s exposure to the harsh conditions of space including radiation, extreme temperatures, high vacuum, micrometeoroids, orbital debris, and more. The use of BCIs would not only reduce the number of interfaces and improve communication within the craft, but it would also allow for more efficient exploration and operations through the monitoring and control of rovers, scouts, probes, robots, and other systems (Negueruela, Broschart, Menon & Millan, 2011). As stated, an additional service that the BCI technology would provide is the continuous health monitoring of astronauts. Upon enabling a real-time check of brain functionalities, the post-processing of brain signals could give fundamental insights into the astronaut health state including tiredness and loss of attention which could be monitored to prevent inaccurate operations and erroneous commands, as well as a faster control and easier command error correction (Negueruela, Broschart, Menon, and Millan, 2011).

Although the brains adaptation to such a link for long-duration and high-risk space operations is largely unknown, researchers Moxon and Foffani (2015) assume that the brain will eventually adapt and manipulate its neurophysiological activity to improve invasive BCI performance while the BCI system develops to gain control over all functions, both human and craft, in case of emergencies. This, however, is still an untested hypothesis. As countered by Negueruela, Broschart, Menon, and Millan (2011), a non-invasive BCI approach is much more suitable for current space applications as it has a more favorable public perception, requires a shorter time for qualification, does not require surgical operations, as is currently much safer for the astronaut. Despite this, it is hoped that safe and effective invasive BCIs are developed and utilized for future space operations, being that this technology acquires a greater amount of information signals that enable higher performance limits (Kotchetkov et al, 2010). These strong claims and recommendations make it essential to assess the various limitations and assessment measures of the BCIs in this unique and complex application.

Limitations, Assessments, and Operation Evaluations

Despite the technological advances, many challenges remain to employ BCIs for completing reliable and efficient human spaceflight tasks. As researchers Gemignani, Gheysens, and Summerer (2015) outlined, a few of the common challenges include low information transfer rates, extensive training time for users, and changes in the user’s brain activity due to fatigue or distraction. Being that BCI technology is typically achieved and optimized in well-controlled experimental conditions (Moxon & Foffani, 2015), there is also a general concern about utilizing these devices in this harsh environment characterized by extreme multitasking and uncertain events. As noted by researchers Negueruela, Broschart, Menon, and Millan (2011), variability and changes in brain functions, emotional states, the use of medication, and medical conditions are other influencing mission factors that need heavy consideration. There are also general concerns regarding the system designs of BCIs for this application such as having wrong and undesired associations of different user inputs causing unreliability and a lack of user satisfaction.

Exploring the limitations and drawbacks of the non-invasive, invasive, and partially invasive BCIs are also essential to future space operations. A central drawback for space systems relying on these devices is the lengthy training time (several weeks to several months) required for the subjects to achieve satisfactory performance and in cases with external stimulations, a fatigue phenomenon has been reported by subjects and researchers (Abiri et al., 2017). Moreover, as researchers Kotchetkov et al. (2010) outlined, non-invasive BCIs relying on EEG devices are fundamentally limited by their signal content which does not convey information about components of movement such as position and velocity, and recordings are prone to interference from the electromyographic activity of cranial musculature. Major shortcomings of invasive BCIs, as explained by Kotchetkov et al. (2010), are associated with the loss of signal reliability over time due to damage incurred by damage at the site of insertion, movement, changes in brain volume, physical activity, and other factors. As a result, the length of time over which an implantable electrode can produce signals is measured in months and typically does not make it over one year without significantly losing quality (Kotchetkov et al., 2010). Invasive or partially invasive BCIs also present an ethically challenging scenario that raises concerns of risk, neurocognitive enhancement, and the alteration of personal identity (Kotchetkov et al., 2010). Due to these anatomic and cognitive error potentials, understanding the full scope of the developed BCI devices and their situational implementation is extremely necessary for improved performance in space.

With this, employing effective assessment and evaluation techniques is a central factor to successful space operations with BCIs. Not only can astronauts learn to control their brain activity and EEG patterns through appropriate training sessions for BCI devices which greatly improves operational performance (Negueruela, Broschart, Menon, & Millan, 2011), but machine-learning approaches can be embedded and used within the BCI to monitor, assess, and evaluate both the operation and overall performance. Moxon and Foffani (2015) reinforced this, stating that complementing this control with the explicit addition of somatosensory feedback and direct interaction will likely provide the subject with a more natural, safe, and effective experience that engages and motivates participation from the operator in specific tasks, thus achieving the targeted performance. It is also suggested that the system be integrated with neurofeedback exercises to improve cognitive functioning (Abiri et al., 2017), as well as incorporating specific rejection criteria that assists in avoiding risky decisions (Negueruela, Broschart, Menon & Millan, 2011). These implementations would not only ensure system and user safety but also assist in operational functions and achieving mission success.

Conclusion

As a new approach for the organization of astronaut control systems and operations, the use of BCI technology would allow for increased efficiency, reliability, and usability of the astronaut’s system and task interfaces. Specifically, it is suggested that non-invasive BCIs be considered for use in current space operations for increased communication, control, and astronaut monitoring. This is mainly due to its inexpensive and inconspicuous characteristics; however, it is expected that improvements to these devices are made, leading to more ergonomic, sustainable, and unobtrusive BCI devices for space operations. There should also be an overall goal of improving invasive BCIs for this specific application so more encompassing and reliable data can be collected during space operations that furthers research and exploration endeavors. Along with a more direct interface link and a better performance overall, the use of invasive BCIs should eventually allow for cost-efficiency, safety, sustainability, and reliability in future space operations.

Recommendations for Future Research

Additional research and testing are needed to understand the effects that non-invasive and invasive BCIs have on the human brain and overall performance in space operations, as well as the inter-workings, limitations, capabilities, and specific designs of BCI technology for this complex application. As suggested by Moxon and Foffani (2015), more research is also needed into neurophysiological activity within the brain, changes in neuronal tuning properties during learning, brain-machine adaptations, and the presence or onset of neurological disorders. Conducting more research to understand this complex connection between humans and machines within the space environment, specifically the utilization of BCI technology for operational purposes, is a fundamental endeavor for achieving active, sustainable, and efficient operations in space.

References

Abiri, R., Zhao, X., Heise, G., Jiang, Y., & Abiri, F. (2017, May). Brain computer interface for gesture control of a social robot: An offline study. In 2017 Iranian Conference on Electrical Engineering (ICEE) (pp. 113-117). IEEE.

Clynes, M.E. and Kline, N.S., 1960. Cyborgs and space. Astronautics, 26–27, 74–76.

Gemignani, J., Gheysens, T., & Summerer, L. (2015, August). Beyond astronaut’s capabilities: The current state of the art. In 2015 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC) (pp. 3615-3618). IEEE.

Kotchetkov, I. S., Hwang, B. Y., Appelboom, G., Kellner, C. P., & Connolly, E. S. (2010). Brain-computer interfaces: military, neurosurgical, and ethical perspective. Neurosurgical focus, 28(5), E25.

Moxon, K., & Foffani, G. (2015). Brain-Machine Interfaces beyond Neuroprosthetics. Neuron, 86(1), 55-67. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.036

NASA, 2018. 5 hazards of human spaceflight videos. Available from: https://www.nasa.gov/hrp/hazards

Negueruela, C., Broschart, M., Menon, C., & Millán, J. D. R. (2011). Brain–computer interfaces for space applications. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 15(5), 527-537. doi:10.1007/s00779-010-0322-8

Pecora, A., Minotti, L. M. A., Ruggeri, M., Dariz, L., & Ferrone, A. (2016, June). Advances in human machine safe interaction: How these technologies can be applied in astronautics. In 2016 IEEE Metrology for Aerospace (MetroAeroSpace) (pp. 146-150). IEEE.

Szocik, K., & Braddock, M. (2019). Why human enhancement is necessary for successful human deep-space missions. The New Bioethics, 25(4), 295-317.

Originally created by Samantha Colangelo to fulfill requirements for Embry Riddle Aeronautical University’s Master of Science program in Human Factors. December, 2020.