This paper investigates the effects of spaceflight stressors on an astronaut’s operational performance during extended missions. In addition to exploring an average astronaut’s homeostatic range, the relationship between various space stressors and astronaut physiology is also investigated. Through an extensive literature review, this paper outlines an individual’s physiological functions and performance during prolonged spaceflight and includes the circulatory, respiratory, nervous, and sensory-motor systems. In addition to exploring the various countermeasures used to combat spaceflight effects, several suggestions were proposed to assist in an individual’s stress response and overall coping skills. This includes artificial gravity, the implementation of wearable biosensor devices for monitoring physiological responses, virtual reality (AR) and augmented reality (AR) for training optimization, communication support, and stress-relief, as well as intentional light exposure, the production of nutrient-dense food, and more comprehensive exercise programs to sustain the overall wellbeing of the crewmembers. To conclude, various calls for further research were also suggested such as pregnancy and child development in space, as well as aging and the elderly.

Keywords: Stressor, Stress, Physiology, Homeostasis, Astronaut, Spaceflight

Stressors of Extended Spaceflight on Astronaut Physiology

Although several technological advancements have been made to ensure the short-term survival of humans in the complex environment of space, there is still a multitude of physiological hurdles that astronauts need to overcome for efficient long-term operations. Extending the duration of spaceflight from months to several years will challenge human capabilities in all aspects and with an increase in both commercial space travel and prolonged manned missions, it is crucial to understand the various stressors of spaceflight and the physiological effects on the human body. Despite much of the research conducted in space centering around the human body’s changes and adaptations to the environment, there is still so much that is unknown about the effects of long-term exposure to spaceflight stressors on the human body. Developing better countermeasures and more effective interventions to sustain life in a spaceflight environment is necessary for the continued expansion of the human species, although understanding the complex stressors of space and effects on the human body is the first step towards enabling people to travel safely in space for extended periods.

Space Stressors

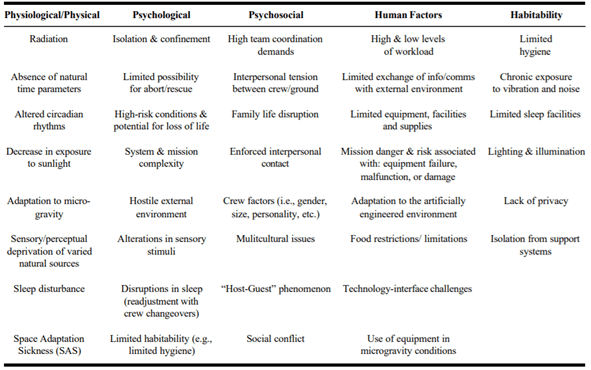

Space is an extremely harsh environment characterized by several environmental stressors that cause unique alternations in human physiology and homeostasis. The stressors of spaceflight, including fluctuations in air pressure and temperature, microgravity, radiation, isolation, and confinement (see Table 1 below), have significant impacts on the wellness and performance of astronauts. These stressors, although already taxing, are exacerbated by mission length, age, gender, pre-existing health conditions, and vehicle configuration (Pelligra & Edemekong, 2017).

Table 1

Physiological, Psychological, and Human Factor Stressors of Spaceflight

In addition to the extensive list of space stressors outlined in Table 1 above, a dangerous aspect of prolonged spaceflight is the chronic, self-imposed stress experienced by the crewmembers. As Won and Kim (2016) outlined, chronic stress is a subjective, threatened state that can persist for days, weeks, or months following exposure to extrinsic or intrinsic adverse forces. Due to our emotional and behavioral responses to different situations, this stress is often intrinsically derived and inflicted upon ourselves. Although short-term stress can be healthful and helpful in solving problems by causing us to stay focused, energetic, and alert, long-term chronic stress can cause a lack of coordination between the human body and the mind while reducing productivity (Alhitary, Hay, & Al-bashir, 2018), as well as other severe physiological and psychological effects including heart attacks and strokes, headaches, high blood pressure, memory impairment, depression, and anxiety (Bryce, 2001).

As clearly shown, this environment poses several challenging hurdles and health risks for achieving prolonged spaceflight. These stressors, which can potentially lead to psychological and physiological declines, may also lead to performance decrements and serious errors that could endanger the mission, craft, and crew. Understanding the impact that these stressors have on the physiological functioning and homeostatic state of humans in prolonged spaceflight, although extensive and undoubtedly challenging, is the first step toward achieving extended spaceflight operations and space tourism.

Astronaut Homeostasis and Physiological Processes

The various stressors of spaceflight have immense effects on the homeostatic state of astronauts, especially when exposed for long durations. As outlined best by Davies (2016), homeostasis is a characteristic of a living system that regulates its internal environment and maintains a somewhat stable, constant condition of properties. Examples of homeostatic states regarding human physiology in space include the individual’s core body temperature, blood pressure, and oxygen content. This paper will review the effects of these spaceflight stressors on human physiological functioning and homeostatic states, particularly with the cardiovascular, respiratory, nervous, and sensory-motor systems.

Cardiovascular System

Spaceflight, both short and long duration, has significant effects on the human’s cardiovascular system. Also called the circulatory system, the cardiovascular system is primarily responsible for the shifts in body fluids. As Woodrow and Webb (2011) define, the human circulatory system is a closed and continuous loop system composed of the blood, the heart, and the conducting vessels: arteries, arterioles, capillaries, venules, and veins. As further described by Woodrow and Webb (2011), the cardiovascular system’s primary function is to serve as the transportation system within the body; however, it also contributes to other functions such as thermoregulation and defense against pathogens.

Many changes occur to this physiological system when exposed to the spaceflight environment, with the main symptom being fluid redistribution. As thoroughly outlined by Williams, Kuipers, Mukai, and Thirsk (2009), the human body experiences redistribution of fluid to the torso and head with a 10% decreased fluid volume in the legs, while twenty-four hours after the launch, the body experiences a 17% reduction in plasma volume. After about a month of space habitation, there is a gradual decrease in erythropoietin secretion which leads to a 10% decrease in total blood volume, and once back on Earth, a state of orthostatic hypotension occurs from the pooling of fluids in the legs; however, in about twenty-four to forty-eight hours after the return to Earth, the body returns to a normal distribution of fluid (Williams, Kuipers, Mukai, & Thirsk, 2009). In addition to the redistribution of body fluids and loss of both plasma and blood volume, other symptoms of these cardiovascular issues include reduced heart rate and diastolic pressure, cardiac dysrhythmias, amnesia and confusion, convulsions and seizures, dizziness and vision issues, as well as post-flight hypovolemia, postural hypotension, and orthostatic intolerance (Blader, 2010). Although more research needs to be conducted for prolonged travel, the known causes of these well-documented cardiovascular symptoms of spaceflight are attributed to the exposure of microgravity and excessive acceleration, as well as the considerable amount of stress and reduced fluid intake that accompanies current spaceflight (Blader, 2010).

Respiratory System

The respiratory system is another critical physiological structure affected by the stressors of spaceflight. As defined by Woodrow and Webb (2011), the respiratory system includes the body’s airways, lungs, and blood vessels with its primary function being to uptake oxygen (O2) and remove carbon dioxide (CO2). Despite the harsh condition of outer space and the respiratory system’s particular sensitivity to the environment, this system is one of the few physiological functions that does not suffer from serious degradation from prolonged exposure to microgravity (Prisk, 2014).

A research study done by Baranov, Tikhonov, and Kotov (1992) found that astronauts in prolonged spaceflight generally experience a decrease in lung volume and breathing mechanics. This was corroborated by researchers Baevsky et al. (2007) with their findings that lung volumes are reduced during spaceflight while vital capacity and respiratory muscle strength were able to be maintained during long-term spaceflight. Since crewmembers are currently exposed to levels of carbon dioxide that are ten-fold higher than those experienced on Earth (Roy-O’Reilly, Mulavara, & Williams, 2021), there are also some reports of changes in the thorax wall and respiratory mechanics, as well as the reduction in rib cage expansion (Demontis, et al., 2017). Furthermore, there is concern about the effects of extreme acceleration and increased gravitational force (g-force) on respiratory functioning, specifically regarding the compromise of chest wall mechanics, the disruption of the anatomical integrity of the lungs, and even shortness of breath or hypoxemia (Woodrow & Webb, 2011). However, a more recent study done by Prisk (2014) discovered that there is a slight increase in pulmonary functioning due to microgravity and the craft’s air pressurization. Furthermore, Prisk (2014) found that unlike other physiological systems, the lungs do not appear to undergo adaptive structural changes when gravity is removed and in addition to this lack of degradation, the gas exchange that happens during pulmonary circulation seems no more efficient than on Earth.

Nervous System

The human body’s nervous system is another main physiological function that is greatly affected by the known spaceflight stressors. As Woodrow and Webb (2011) describe, the nervous system is characterized by a complex network of nerves and cells that maintains homeostasis by recording and distributing information throughout the body. Not only does the nervous system assist in controlling the sensations of feeling and breathing, but also functions like walking, thinking, and eating (Woodrow & Webb, 2011). To better describe these various functions, the nervous system is divided into two processes: the central nervous system (CNS) and the autonomic nervous system (ANS).

The CNS, as outlined by Jandial, Hoshide, Waters, and Limoli (2018), consists of the brain and spinal cord which controls receiving and sending messages throughout the body which can adapt and compensate under altered stimulus conditions, such as those experienced during spaceflight. Despite the importance of this system, the effects of long-duration spaceflight on the CNS and the resulting impact on crew health and operational performance remain largely unknown (Roy-O’Reilly, Mulavara, & Williams, 2021). However, according to researchers Cekanaviciute, Rosi, and Costes (2018) and Jandial, Hoshide, Waters, and Limoli (2018), the most impactful space stressor on the CNS seems to be the increased cosmic radiation which can lead to neuroinflammation, neuronal damage, and cognitive deficits.

In addition to the CNS, the ANS is in control of the body’s automatic processes that occur unconsciously such as breathing, sweating, and even pupil dilation (Mandsager, Robertson, & Diedrich, 2015). Despite subtle changes in autonomic activity during spaceflight, as further outlined by researchers Mandsager, Robertson, and Diedrich (2015), the underlying circulatory and hormonal factors of the autonomic nervous system seem to remain intact. With this, some alterations in nervous tissue function are transient while some are longer-lasting; however, many of these changes are behaviorally useful adaptations to the new environmental demands (Kalb & Solomon, 2007). Despite this, some of these alterations degrade sensory skills and motor performance.

Sensorimotor System

An astronaut’s ability to balance, sense, perceive, and control motor functions are also affected by long-term exposure to spaceflight conditions. The sensorimotor system, characterized by sensory processes and motor functions, has shown several physiological changes attributed to these conditions. Other than the study conducted by Taylor et al. (2020) showing evidence that an astronaut’s sense of taste changes during spaceflight, there has been little clinical research conducted in space on the gustatory system, hearing, or the olfactory senses. Instead, most of the research into these changes during and after spaceflight centers around the astronaut’s vision, vestibular, and proprioception senses.

Many of the detrimental effects to the sensorimotor system are associated with microgravity, lack of light, and deficient nutrition. As researchers Jandial, Hoshide, Waters, and Limoli (2018) discovered, the intracranial pressure and the disequilibrium experienced by astronauts cause visual changes associated with anatomic disfigurements of the globe and optic nerve, which can also lead to impairments in the astronaut’s heart rate, blood pressure, breathing patterns, gaze control, as well as cause extreme nausea, vomiting, and fatigue. Reinforcing this, researchers Clement, Skinner, and Lathan (2013) found that astronauts often experience distortions in visuospatial constructs, perceptual-motor constructs, and the mental representation of spatial cues. Considering that visual references are vital to an astronaut’s orientation during spaceflight (Blaber, Marcal, & Burns, 2010), it is unsurprising that astronauts experience negative alternations in the vestibular and proprioception senses.

The vestibular sense, or the human’s ability to find balance, as well as proprioception, or the human’s sense of self-movement and body position is largely associated with the inner ear and is greatly affected under the conditions of space. The effects of microgravity on these systems are quite extensive and include the deconditioning of posture, gait control, and motion sensors, as well as an altered perception of orientation and the loss of balance (Blaber, Marcal, & Burns, 2010).

As researchers Blaber, Marcal, and Burns (2010) explain further, the absence of gravity results in misleading signals from the central vestibular system, peripheral pressure receptors, and visual cues which occurs to a point where disorientation, dizziness, vertigo, headaches, cold sweating, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting occurs, otherwise known as a condition called space adaptation syndrome (SAS) or space motion sickness (SMS). This type of space sickness occurs when there is a mismatch between the visual and neuro-vestibular perception of motion (Williams, Kuipers, Mukai, & Thirsk, 2009). The long-term deprivation of the vestibular senses seen in extended spaceflight also results in adaptations to the thalamocortical vestibular system including areas involved in cognitive functions and sensory integration (Roy-O’Reilly, Mulavara, & Williams, 2021). In addition to these physiological changes, researchers Roy-O’Reilly, Mulavara, and Williams (2021) describe notable alterations in the performance of sensorimotor and spatial working memory task changes, as well as decreases in neural efficiency during vestibular stimulation amid extended space flight.

The effects of spaceflight stressors on the human body’s motor functions and musculoskeletal system are also extensive and include decreased bone formation, muscle mass, and functional capacity with increases in bone resorption, muscle fatigue, and post-flight muscle fiber necrosis (Blaber, Marcal, & Burns, 2010). This development of muscle atrophy and the reduction in peak force and muscular power can be first detectable within days of existence in microgravity and progresses throughout the mission (Kalb & Solomon, 2007). As Williams, Kuipers, Mukai, and Thirsk (2009) describes, there is a gradual decrease in muscle mass by 20% during the first 24 hours in space, and after about a month of habitation, 30% of muscle mass decreases by 30%. As the duration of the mission lengthens, both flexor and extensor muscles are weakened (Kalb & Solomon, 2007), with the postural muscles being most affected by spaceflight (Williams, Kuipers, Mukai, & Thirsk, 2009). The three factors that underlie this observed decrease in strength are the removal of antigravity loads, the reduction in neural drive to the muscles, and the microgravity-induced change in motor control and coordination (Kalb & Solomon, 2007). There are also notable losses of bone density during longer missions, with bone demineralization beginning immediately on arrival in space and continuing throughout the mission, with a noted 60%–70% increase in urinary and fecal calcium (Williams, Kuipers, Mukai, & Thirsk, 2009). In addition to these physiological effects, astronauts gain roughly two to three inches in height during a mission, mostly during the first ten days of flight, which is likely to occur with changes in the thorax (Kalb & Solomon, 2007).

Despite these changes, astronauts typically work through muscle soreness and tightness to eventually make a full recovery of strength and muscle mass once back on Earth. However, the loss of bone density may continue despite the intensive and lengthy recovery process, with most astronauts on long-duration missions fully recovering their bone density within three years after a flight and some never regaining their preflight levels (Williams, Kuipers, Mukai, & Thirsk, 2009). There is also a general concern for all astronauts developing early-onset osteoporosis and increased bone fractures (Williams, Kuipers, Mukai, & Thirsk, 2009). The absence of gravitational loading on bones and muscles during spaceflight, as well as the lack of light, suboptimal nutrition, and increased stress, is thought to be the fundamental causes of these biochemical and structural changes to the human body (Williams, Kuipers, Mukai, & Thirsk, 2009). Despite virtually all individuals who spend weeks or months in space experience loss of strength and muscle, decreases in bone density, and other physiological effects, optimal exercise programs have not yet been established (Kalb & Solomon, 2007). It should also be noted that although most of these sensorimotor changes are greatest immediately after gravitational transitions, the extent and duration of some of these alterations are associated with increased mission length (Roy-O’Reilly, Mulavara, & Williams, 2021).

Astronaut Performance

While the advances in technology have allowed space exploration and habitation for longer durations, the impact of these spaceflight stressors on the human body have presented a range of challenges that need addressing for the future of safe and effective operations. Since the success of long-duration stays in space largely depends on the health and operational performance of individuals and multinational groups while under hazardous spaceflight stressors, these decrements in performance must be assessed.

Although the declines in performance are believed to be temporary and the symptoms caused by the spaceflight environment have not yet reached clinical levels, there have been instances of impaired performance capacity, significant conflict among crew members, and errors in performing operational tasks (Morphew, 2001). Sensorimotor dysfunction, specifically, has been implicated as a major potential cause of performance decrements during and after spaceflight and has caused notable effects on cognitive, information processing, memory, psychomotor, and physical capabilities (Roy-O’Reilly, Mulavara, & Williams, 2021). As reinforced by Morphew (2001), research has found that the spaceflight environment itself does not lead to any notable or worrisome performance changes except for sensorimotor functions, specifically being hand-eye coordination during the adaptation phases to microgravity and Earth. A separate issue, as identified by Morphew (2001), is that even though the environment itself does not lead to significant performance changes, the operational mission environment does which includes periods of exceptionally high workload, fatigue, chronic noise, and temperature changes from the craft, stress, and lack of privacy. Although these challenges have been met with remarkable success despite the adverse circumstances, the human element remains the most complex component in the success of long-duration missions into space (Evans & Ball, 2001).

With this, it is important to recognize that despite the astronaut’s exposure to life-threatening stressors, as well as both physiological and psychological effects such as space sickness and headaches, anxiety, anger, and depression, there have been no recent mission failures that can be attributed to health problems or diminished operational performance (Evans & Ball, 2001). However, there is still much that is unknown and misunderstood about prolonged spaceflight on the human body. To better understand the mitigation measures needed to achieve long-duration spaceflight, the currently employed countermeasures need to be examined first.

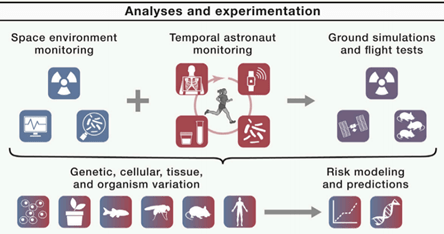

Physiological Assessments and Countermeasures

Mitigating the progression of the adverse physiological effects caused by the stressors of spaceflight has been the central focus of space medicine and human factor research. With astronaut health data being collected for over a decade, it has been revealed that the employed biomedical countermeasures and technological advancements have resulted in significant improvements for most immune and stress parameters (Crucian et al., 2020). The evidence of this mainly comes from three sources, being anecdotal reports from astronauts and cosmonauts, summary information from space agencies on the incidence of adverse health events during space missions, and findings from analog environments such as crews aboard submarine patrols or wintering over in the Antarctic (Evans & Ball, 2001). Other strategies to analyze and record spaceflight stressors, as well as various experiments that can be conducted with this information, are shown below in Figure 2.

Figure 1

Ways to Record and Analyze Spaceflight Data

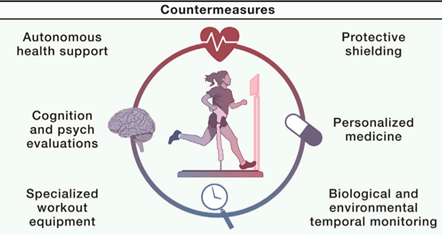

Utilizing effective measures that identify and mitigate the known stressors of spaceflight is crucial for ensuring an astronaut’s safety and optimal performance for a successful mission. As Crucian et al., (2020) outlines, the current countermeasures that have been deployed to address the stressors and health issues in space include technological advancements such as protective shielding, as well as improved aerobic and resistive exercise equipment, psychological and pharmaceutical support for crewmembers, and more frequent resupplies and nutritional supplementations. It is also important to note that specific countermeasures are employed to combat specific stressors and effects of spaceflight. As Williams, Kuipers, Mukai, and Thirsk (2009) describes, astronauts are required to partake in exercise, use liquid cooling garments, as well as negative pressure suits for the lower body to mechanically induce a correct body fluid distribution during re-entry to earth and midodrine to counter postflight orthostatic intolerance to mitigate the cardiovascular effects of spaceflight. To combat the neuro-vestibular effects of spaceflight, astronauts undergo environmental conditioning through VR or parabolic flights and are prescribed both antinausea medications and fluid administrations (Williams, Kuipers, Mukai, & Thirsk, 2009). The muscular and skeletal changes that happen to the body are mitigated through resistance and aerobic exercise programs, dietary supplementation, electrical muscle stimulation, and both muscle conditioning and rehabilitation after flight including massages, icing, and other adapted exercises (Williams, Kuipers, Mukai, & Thirsk, 2009). Although resistive exercises are thought to be the most effective method of maintaining muscle mass and strength in space (Hargens, Bhattacharya, & Schneider, 2021), more effective countermeasure programs are likely multimodal and include exercise, hormonal, nutritional, and pharmacologic interventions tailored to the individual (Kalb & Solomon, 2007).

Figure 2

Various Countermeasures for Human Health in Space

Although many of the spaceflight stressors have been addressed and sufficiently mitigated through these various countermeasures employed by crewmembers and space organizations, there are still several effects that are unknown and misunderstood. It is also important to note that the available evidence-based data from space missions are currently insufficient for the objective evaluation or projection of the health issues likely to be involved in long-duration space missions (Evans & Ball, 2001). As further outlined by Hargens, Bhattacharya, and Schneider (2012), many of the current countermeasures’ ineffectiveness can be attributed to the inadequacies of current flight exercise hardware. The unique environment has also proved constrictive for researching in the real context, which needs to be considered when designing new or additional mitigation measures.

Optimizing Physiological Performance in Space

The gaps in current stress and physiological risk countermeasures must be addressed to optimize the physiological performance of astronauts during extended spaceflight. Despite the modern procedures and recommendations, several other effective mitigation strategies can inspire more efficient coping and stress response skills, such as supportive and wearable technologies, intentional light exposure, improved fitness routines, and more nutritious diets. These implementations, along with continual, meaningful, and variable tasks to support cognition and enhance motor skills, would hopefully aid positive interpersonal interactions and the overall wellbeing among crewmembers.

The various technological advancements made this past decade have led to several suggestions for optimizing human health in space. One of the most useful and applicable technologies that have been explored by NASA, as well as other agencies, have been wearable monitoring devices such as wristbands (Ralls, 2021), exoskeletons (Whiting, 2018), and spacesuits (Anderson, 2020). These wearable physiological monitoring systems and biosensor devices will track the health and performance status of astronauts through the measuring of activity patterns and conventional vital signs (e.g. heart rate, blood pressure, body temperature), where the collected data from these devices is converted into useful and actionable information for medical management, safety monitoring, decision-support, and performance optimization (Sawka & Friedl, 2018). Implementing brain-computer-interfaces is another suggestion that would allow for more direct control of craft systems, assist in efficiently monitoring and assessing physiological factors, as well as improve communication and understanding among the crewmembers. This technology can not only be used by astronauts to overcome the communication difficulties in spacesuits and noisy environments but also by individuals who have lost their voice or suffer from permanent speech difficulties. As outlined by researchers Hassanien and Azar (2015), these non-invasive and EEG-based systems can be achieved through small button-sized sensors that are fixated under the jawbone of either side of the throat to collect vital signals which are sent to processors and computer program that translates into words.

The use of Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) are other practical technological applications that could assist in the physiological and psychological wellbeing of astronauts. Not only do these devices create simulated worlds that can facilitate interpersonal communication, provide various forms of entertainment and exercise, and assist in the education and training of crewmembers but they can also relax users in a private and confidential setting as a means of escape from daily sources of stress (Salamon, Grimm, Horack, & Newton, 2018). This specific technology, as outlined by Salamon, Grimm, Horack, and Newton (2018), can also be used in conjunction with monitoring technologies to become a responsive and rehabilitative system, making it a plausible measure in preventing cognitive deteriorations in astronauts during extended spaceflight. Although there is also the suggestion of creating artificial gravity, which would address many of the physiological stressors experienced, this is quite a large and collaborative venture. As Clement, Bukley, and Paloski (2015) note, the concept of artificial gravity is to provide a broad-spectrum replacement for the gravitational forces that naturally occur on the Earth’s surface which thereby avoids the physiological deconditioning that occurs in weightlessness. Many hope that by approximating the normal Earth’s gravitational environment through centrifugation or partial-gravity simulators, an all-encompassing countermeasure would be offered to address the debilitating and potentially fatal problems of bone loss, cardiovascular deconditioning, muscle weakening, sensorimotor and neuro vestibular disturbances, and regulatory disorders (Clement, Bukley, & Paloski, 2015).

To provide more natural countermeasures to the physiological stressors of extended spaceflight, many calls have been made to implement light exposure therapy for the crewmember’s physiological wellbeing, as well as providing more nutritional dietary choices and impactful exercise programs. Although bright fluorescent white lighting is used as a countermeasure during pre-launch activities, there has been an increasingly large call for utilizing it within spacecrafts to mitigate the disturbances in circadian rhythm and altered sleep-wake patterns (Brainard et al., n.d.). As reinforced by researchers Brainard et al., (n.d.), finding the ideal spectral distribution and light wavelengths for the illumination of general living quarters and therapy measures is necessary for optimal physiological functioning during prolonged space exploration. This research and implementation would also assist in the production of fresh, nutrient-dense food for sustaining prolonged habitation in space. With a clear inadequate dietary intake, the nutritional status of astronauts is compromised during and after spaceflight with notable decrements in physiological performance. However, as outlined by researchers Smith and Zwart (2008), maintaining nutrition and energy intake on a spacecraft for long durations is possible through understanding the specific requirements for space travelers and ensuring that the food system contains adequate nutrients with palatable foods, that no deficiencies or excesses exist, and that the nutrients are stable throughout the flight. This, in addition to the implementation of additional exercise routines including yoga and breathing techniques, is suggested to mitigate the various musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, and respiratory effects of long-duration spaceflight. The addition of these physical regimes, being yoga breathing, stretching, meditation, and relaxation techniques, may be powerful stress management and rehabilitative tools to counteract the harsh effects of spaceflight (Vernikos, et al., 2012).

To assess the risk factors of prolonged spaceflight for enhancing and optimizing an individual’s physiological performance, it is necessary to develop specific assessment plans and mitigation routines suited for adults of both sexes, as well as children and the elderly. For long-duration flights, it is also suggested that protocols be developed for individuals with various physical and cognitive disabilities. With the development of these various preflight, postflight, and during-flight assessments and mitigation measures, the individuals undergoing these extended voyages across the uniquely harsh spaceflight environment can be better cared for, promoting every crewmember’s health and wellbeing. Developing these measures, however, will prove to be no easy task and will require both collaboration and transparency across many disciplines.

Conclusion

After more than four decades of research and human exploration in space, the greatest fundamental insights gained thus far revolve around the diverse biological responses to complex spaceflight conditions. With greater rates of brain structure and homeostatic changes being recorded with longer mission durations (Roy-O’Reilly, Mulavara, & Williams, 2021), predicting human adaptations and creating predictive measures becomes even more necessary. As best summarized by Kalb and Solomon (2007), the consequence of insufficient weight being given to the biological responses to prolonged existence in space include mission jeopardization and unnecessary lives lost. The most impactful spaceflight stressors, as outlined by Patel et al. (2020), includes space radiation health effects of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and cognitive decrements, Spaceflight-Associated Neuro-ocular Syndrome, behavioral health and performance decrements, and inadequate food and nutrition which are all linked to over thirty documented human health risks (Patel et al., 2020). Not only is an astronaut’s physical coordination, strength, and performance affected during spaceflight, but so are their brain structure and cognitive functions. This makes the employment of effective physiological countermeasures before, during, and after spaceflight essential to reducing the consequences and health risks associated with extended missions. As Prisniakova (2004) outlined, current success in the control of spacecraft systems, astronaut health, and overall mission depends on the personal qualities of astronauts and their training standard, a prediction of their behavior and adaptations to these extreme conditions and stressors, as well as the operational environment and organization of the living and working conditions. Despite the current measures and their utility, other physiological mitigation measures need to be created and enforced, including wearable biosensors, VR and AR technologies, artificial gravity, light exposure optimization, food production, and exercise programs.

By first recognizing that spaceflight effects on biological systems are incredibly profound, the consequences of long-duration spaceflight stressors can be increasingly researched and hopefully avoided. The challenge in the context of long-duration spaceflight is the adaptation to circumstances that never existed during the evolution of life on Earth or during any human’s development. In addition to overcoming financial constraints, as well as organizational and political restrictions, collaboration among physiologists, engineers, and various subject matter experts is necessary to achieve this health and performance optimization. Further research also needs to be conducted regarding the different physiological variations between the different sexes during prolonged spaceflight, pregnancy and child development, aging and the elderly, as well as the current condition of sleep quality and memory processes under these complex conditions. In addition to this, there is a large need to conduct further research in the real spaceflight environment. Creating and implementing these various mitigation measures outlined above, as well as following the various calls for further explorations, will hopefully allow the human species to overcome the limitations of long-duration space habitation and exploration to achieve a long life among the stars.

References

Alhitary, A., Hay, E., & Al-bashir, A. (2018). Objective detection of chronic stress using physiological parameters. Medical & biological engineering & computing, 56(12), 2273-2286.

Anderson, L. (2020, January 03). Spacesuits are the ultimate wearable technology. Retrieved March 07, 2021, from https://lstarkweather.medium.com/spacesuits-are-the-ultimate-wearable-technology-47ddb89088df

Baevsky, R. M., Baranov, V. M., Funtova, I. I., Diedrich, A., Pashenko, A. V., Chernikova, A. G., … & Tank, J. (2007). Autonomic cardiovascular and respiratory control during prolonged spaceflights aboard the International Space Station. Journal of Applied Physiology, 103(1), 156-161.

Baranov, V. M., Tikhonov, M. A., & Kotov, A. N. (1992). The external respiration and gas exchange in space missions. Acta Astronautica, 27, 45-50.

Blaber, E., Marçal, H., & Burns, B. P. (2010). Bioastronautics: the influence of microgravity on astronaut health. Astrobiology, 10(5), 463-473.

Brainard, G., Fucci, R., Tavener, S., Byrne, B., Hanifin, J., Jasser, S., … & Rollag, M. (n.d.) Optimizing Light Spectrum for Long Duration Space Flight. Thomas Jefferson University.

Bryce, C. P. (2001). Insights into the concept of stress. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization.

Cekanaviciute, E., Rosi, S., & Costes, S. V. (2018). Central nervous system responses to simulated galactic cosmic rays. International journal of molecular sciences, 19(11), 3669.

Clément, G., Bukley, A., & Paloski, W. (2015). Artificial gravity as a countermeasure for mitigating physiological deconditioning during long-duration space missions. Frontiers in systems neuroscience, 9, 92.

Clément, G., Skinner, A., & Lathan, C. (2013). Distance and size perception in astronauts during long-duration spaceflight. Life, 3(4), 524-537.

Crucian, B., Makedonas, G., Sams, C., Pierson, D., Simpson, R., Stowe, R., … & Mehta, S. (2020). Countermeasures-based Improvements in Stress, Immune System Dysregulation and Latent Herpesvirus Reactivation onboard the International Space Station–Relevance for Deep Space Missions and Terrestrial Medicine. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews.

Davies, K. J. (2016). Adaptive homeostasis. Molecular aspects of medicine, 49, 1-7.

Demontis, G. C., Germani, M. M., Caiani, E. G., Barravecchia, I., Passino, C., & Angeloni, D. (2017). Human pathophysiological adaptations to the space environment. Frontiers in physiology, 8, 547.

Evans, C., & Ball, J. (2001). Safe Passage: Astronaut Care for Exploration Missions. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/10218

Hargens, A. R., Bhattacharya, R., & Schneider, S. M. (2013). Space physiology VI: exercise, artificial gravity, and countermeasure development for prolonged space flight. European journal of applied physiology, 113(9), 2183-2192.

Hassanien, A., & Azar, A. (2015). Brain-computer interfaces. Switzerland: Springer, 74. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-10978-7.

Jandial, R., Hoshide, R., Waters, J. D., & Limoli, C. L. (2018). Space–brain: The negative effects of space exposure on the central nervous system. Surgical neurology international, 9.

Kalb, R., & Solomon, D. (2007) Space Exploration, Mars, and the Nervous System. Archives of Neurology, 64(4), 485-490.

Mandsager, K. T., Robertson, D., & Diedrich, A. (2015). The function of the autonomic nervous system during spaceflight. Clinical Autonomic Research, 25(3), 141-151.

Morphew, E. (2001). Psychological and human factors in long duration spaceflight. McGill Journal of Medicine, 6(1).

Patel, Z. S., Brunstetter, T. J., Tarver, W. J., Whitmire, A. M., Zwart, S. R., Smith, S. M., & Huff, J. L. (2020). Red risks for a journey to the red planet: The highest priority human health risks for a mission to Mars. npj Microgravity, 6(1), 1-13.

Pelligra, S., & Edemekong, P. F. (2017). Aerospace, Health Maintenance Wellness.

Prisniakova, L. M. (2004). Fitness to work of astronauts in conditions of action of the extreme emotional factors. Advances in Space Research, 33(8), 1381-1385.

Prisk G. K. (2014). Microgravity and the respiratory system. The European respiratory journal, 43(5), 1459–1471. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00001414

Ralls, J. (2021, February 10). NASA makes fitbit ready for work solution available to support health and safety of astronauts and other mission critical employees During Covid-19 pandemic. Retrieved March 07, 2021, from https://investor.fitbit.com/press/press-releases/press-release-details/2021/NASA-Makes-Fitbit-Ready-for-Work-Solution-Available-to-Support-Health-and-Safety-of-Astronauts-and-Other-Mission-Critical-Employees-During-COVID-19-Pandemic/default.aspx

Roy-O’Reilly, M., Mulavara, A., & Williams, T. (2021). A review of alterations to the brain during spaceflight and the potential relevance to crew in long-duration space exploration. npj Microgravity, 7(1), 1-9.

Salamon, N., Grimm, J. M., Horack, J. M., & Newton, E. K. (2018). Application of virtual reality for crew mental health in extended-duration space missions. Acta Astronautica, 146, 117-122.

Sawka, M. N., & Friedl, K. E. (2018). Emerging wearable physiological monitoring technologies and decision aids for health and performance.

Smith, S. M., & Zwart, S. R. (2008). Nutrition issues for space exploration. Acta Astronautica, 63(5-6), 609-613.

Taylor, A. J., Beauchamp, J. D., Briand, L., Heer, M., Hummel, T., Margot, C., … & Spence, C. (2020). Factors affecting flavor perception in space: Does the spacecraft environment influence food intake by astronauts?. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 19(6), 3439-3475.

Vernikos, J., Deepak, A., Sarkar, D. K., Rickards, C. A., & Convertino, V. A. (2012). Yoga therapy as a complement to astronaut health and emotional fitness stress reduction and countermeasure effectiveness before, during, and in post-flight rehabilitation: a hypothesis. ARMY INST OF SURGICAL RESEARCH FORT SAM HOUSTON TX.

Whiting, M. (2018, February 24). NASA’s newest wearable technology takes on the Human Shoulder. Retrieved March 07, 2021, from https://www.nasa.gov/feature/nasa-s-newest-wearable-technology-takes-on-the-human-shoulder

Williams, D., Kuipers, A., Mukai, C., & Thirsk, R. (2009). Acclimation during space flight: effects on human physiology. Cmaj, 180(13), 1317-132

Won, E., & Kim, Y. K. (2016). Stress, the autonomic nervous system, and the immune-kynurenine pathway in the etiology of depression. Current neuropharmacology, 14(7), 665-673.

Originally created by Samantha Colangelo to fulfill requirements for Embry Riddle Aeronautical University’s Master of Science program in Human Factors. March, 2021.