This document theoretically explores the implementation of technologies and system designs for a spacecrafts crew platform that holistically supports the crewmembers for longer durations. To ensure a holistic and human-centric approach is taken in this design, the spaceflight stressors and associated anthropometric, ergonomic, bio-mechanic, and environmental factors are first explored. Afterward, an explicit description of this crew platform’s design considerations and their requirements are presented, including the chosen human-automation design philosophy to be employed, the display, alerting, and advisory system characteristics, and the various assistive technologies to be used such as the Brain-Computer Interface (BCI), biometric health-monitoring wristband, and the personal assistant agents for scheduling activities and group communication. The crew platform’s information management system is also outlined, as well as the overall interactions between the crew members and these various factors. In short, this document provides a holistic and human-centered platform design for long-duration spaceflight that better supports the crewmembers in conducting their operations and activities, while also maintaining and promoting their overall health and wellbeing.

Keywords: crew platform, system design, human-centric, spaceflight, long-duration

Crew Platform Design Document for Long-Duration Spaceflight

Designing or optimizing a spacecraft is an extremely demanding challenge, and despite the innovative nature of the aerospace industry and the massive technological jumps made in recent years, many of these developments have not yet been implemented in crew platforms or control rooms. This absence can be attributed to many factors, including the current methods of optimization requiring a significant amount of manual customization, the complexity of optimization costs which tends to fluctuate throughout the project, the high level of human expertise needed to achieve good results, as well as the complexity of the task and multidisciplinary nature of the aerospace industry which makes it difficult to obtain a complete survey and understanding of the whole design process and necessary requirements (Fuchs, Girimonte, Izzo, & Neumaier, 2008). Because of this, there is plenty of room for developing more crew-friendly control and platform designs for the progression of human space travel and easing the astronauts taxing workload.

Thus, this Crew Platform Design Document (CPDD) provides a detailed overview and thorough description of a more human-centered multi-crew platform for long-duration deep spaceflight, with innovative and holistic design solutions that aim to support and optimize crew performance. The overall goal of this document is to better understand the associated spaceflight stressors, the ergonomic, anthropometric, biomechanic, and environmental factors, and the industry’s established regulations, requirements, and standards of these aerospace systems, and to then apply this knowledge to the design of a more crew-friendly platform for extended spaceflight. With these understandings, the applied design philosophy, crew platform features, and any challenges, limitations, and mitigation measures are conceptualized and thoroughly described below.

Design Philosophy

Human-rated spacecrafts consist of very complex and often highly interactive physical systems, including multiple propulsion, electrical and mechanical power generation and distribution, flight management, and environmental control and life support (McCann, McCandles, & Hilty, 2005). These systems must perform to precise operational specifications under extremely harsh conditions, making the implementation of automation much more useful. However, as McCann, McCandles, and Hilty (2005) note, virtually any concept of crewmembers interacting with these systems involve some risk to performance, safety, and mission success. This means that defining the specific characteristics and requirements of adaptive and automated system capabilities, especially while the missions continue to increase in duration, is critical to these endeavors.

Thus, the automation philosophy taken in its design will be a hybrid approach centered on both the human and automation within the system. This human/automation approach allows the human to have control and make operationally appropriate decisions with automation working as a supporting role and as a substitute to the operator, taking on the leading controls and system responsibilities if necessary. In taking a human/automated approach to designing this crew platform, the astronaut’s workload is reduced by automating as many tasks as possible with a close-looped system. However, the crew will continuously monitor and maintain this system, meaning it needs to be both interactive and human-centric in its design.

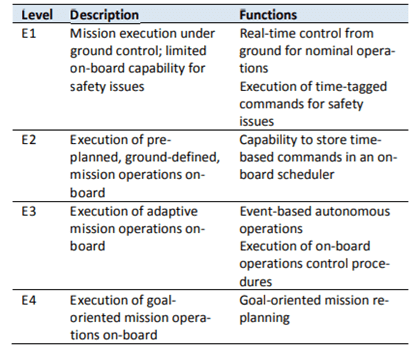

As McCann, McCandles, and Hilty (2005) continue, automating mission operations increases the requirements on crewmembers to act as backups in case of hardware or software failure, while the reverse case is also true in that automation would act as a backup for a human failure, taking over and accomplishing functions that crewmembers normally perform in the event they are incapacitated. With this, Wander & Förstner (2013) note that spacecraft operations today reach the autonomy level E2 shown in Figure 1 below, while the main design philosophy introduced in this document aims at autonomy level E4.

Figure 1.

The European Cooperation for Space Standardization (ECSS) mission execution autonomy levels (Wander & Förstner, 2013).

This mixed-initiative management system means that the automation level would need to drastically increase to the point where the system could execute procedures without human permission. This would act as a fail-safe in ensuring the space flight continues either to its destination or back to Earth despite the crewmember’s status. Considering this system is intended to operate in deep space, it needs to be completely self-sufficient and reliable without human input. As McCann, McCandles, and Hilty (2005) reinforces, the speed-of-light and distance limitations of this deep-space voyage means that all operations and activities need to be performed as real-time collaborations between crewmembers and onboard automation without any assistance from Earth. Taking this hybrid approach in automation will not only ensure the safety of both the crew and the craft, but it will also reduce the operations costs of the spacecraft while improving the ability to do science (Masi, 2003). Therefore, using both the human-centric and automation-centric approaches in designing this crew platform would allow for the most efficient, safe, and supportive environment for the crewmembers and craft.

Limitations and Mitigations

Designing or optimizing a spacecraft is an extremely demanding challenge. As Fuchs, Girimonte, Izzo, and Neumaier (2008) describe best, this can mainly be attributed to the current methods of optimization which require a significant amount of manual customization, the complexity of optimization costs which tends to fluctuate throughout the project, the high level of human expertise needed to achieve good results, as well as the complexity of the task and multidisciplinary nature making it difficult to obtain a complete survey and understanding of the whole design process and requirements. Because of this and other factors, there are many key issues with this automation implementation that needs to be reviewed.

The first legitimate issue to overcome in this scenario, as McCann, McCandles, and Hilty (2005) note, is whether to eliminate human involvement in real-time operations and give full responsibility to machines. There are several compelling reasons why this is not an appropriate operational target, including the inherent risk of entrusting the lives of the crewmembers to software systems, the lack of trust or dependency that the crewmembers may have on the automation, and the potential for removing the humans from the loop which is not the optimal way to utilize valuable onboard human and machine resources (McCann, McCandles, & Hilty, 2005). As McCann, McCandles, and Hilty (2005) affirms, crewmembers are and should continue to be trained in spacecraft operations and the architecture and functioning of vehicle systems until they are subject matter experts, allowing them to contribute to the mission by capitalizing on their strengths, such as adapting and making decisions under adverse and unknown circumstances. These shared responsibilities and controls allow the system to be much more adaptable and efficient, although there is potential for issues in authority to arise.

As McCann, McCandles, and Hilty (2005) describe, authority over procedural retrieval and execution is a major key issue to tackle. Not only does this represent one of the most significant extensions to cockpit automation capabilities over human capabilities, but it also involves the tightest interactions between crewmembers and onboard automation and places the greatest demands on user interface design (McCann, McCandles, & Hilty, 2005). With this increase in automation comes another important problem to address, being the onboard software concerning performance, reliability, and safety. This is especially true as spacecraft design becomes highly sophisticated and complex with future missions including more ambitious goals, demanding performance accuracy and resource availability requirements (Wander & Förstner, 2013).

These ambitious goals result in another pressing issue to overcome in the design process, which is the fact that there is so little known about deep space and the variables that may potentially be faced on such a mission. As Fuchs, Girimonte, Izzo, and Neumaier (2008) outline, accounting for the uncertainties of variables and models that define an optimal and robust spacecraft design and overall successful long-duration mission is a lengthy but necessary process. Uncertainties especially need to be accounted for at an early stage in the design process to critically overestimate or underestimate the spacecraft performances, resulting in having to redesign the craft; however, the available uncertainty information in the early phase of a spacecraft design is often very limited (Fuchs, Girimonte, Izzo, & Neumaier, 2008). As Wander and Förstner (2013) conclude, hardware redundancy methods provide a high level of robustness and good performance that will no doubt assist in mitigating these uncertain variables in the mission, although they often drastically increase the mass and system complexity.

Specific Design Philosophies

With the above principles, limitations, and mitigations in mind, the following statements serve as an explicit outline of the specific design philosophy requirements:

- System authority over the overall operation is divided between the crewmembers and automation, with the human serving as the final authority while they are capable and the automation acting as the support and replacement if needed.

- .All crewmembers are ultimately responsible for onboard safety, research, and monitoring the automated flight systems.

- The automation serves as a tool to aid the crewmembers in safe flight management, with the ability to replace them if needed.

- The system will employ confirmation of command accuracy before automated action execution.

- The automation will give feedback on what it is doing, always keeping the human-in-the-loop.

- The automation will be used in a manner that supports the crewmembers and prevents any loss of skills or performance degradation.

- Crew safety is the top priority, with mission success coming in second, and should not be compromised when allocating tasks or functions.

- The use of new technologies will only be employed for the good of the whole human-machine system and will result in distinct operational advantages.

- The system will be designed to be fault and error-tolerant, simple, interactive, and engineered with redundancy for increased reliability.

Key Documents Establishing Regulations, Requirements, and Industry Standards

To develop aerospace systems and a new crew platform design, there are several regulations and industry standards to be met. Both formal and informal, there are many contributors to ensure a safe spaceflight and an overall successful mission. As noted by Reed (n.d.), the agencies that are primarily responsible for regulating the aerospace sector are the Department of Defense (DOD), Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). For example, the FAA passed a regulation in 2006 regarding commercial spaceflight with specific requirements for crew and spaceflight participant training and consent (Internationale, n.d.), while the EPA has very specific standards for the emissions and air pollutants produced by aerospace facilities (Reed, n.d.). In addition, there are other organizations involved that provide certifications if certain industry standards are met, with the most common being the Nuclear Quality Assurance (NQA). In fact, most organizations operating in the aerospace industry are required to register to one of their specific compliance standards, such as AS9100, AS9110, and AS9120, which covers a wide range of areas, including product safety, configuration management, raw material testing, manufacturing, post-delivery support, and more (“Aerospace Industry Standards,”n.d.).

Another important document that will be used throughout this document is NASA’s Space Flight Human-System Standard (NASA-STD3001) which addresses crew health such as medical care, nutrition, sleep, and exercise, as well as habitability and environmental health such as the design of the facilities, the layout of workstations, lighting requirements, and more (Tillman et al., 2007). In addition to this, a document called the Human Integration Design Handbook (HIDH) also serves as guidance to ensure designers create safe and effective systems that accommodate the capabilities and limitations of spaceflight crews, as well as guidance for human factors requirements for specific aerospace systems (Tillman et al., 2007). In conjunction with these industry standards, the requirements outlined in the FAA’s Advisory Circular (Bahrami, 2010) will also be used in this design document.

One of the other leading standards, although one of the most informal, includes Akin’s Laws of Spacecraft Design. This document consists of forty statements ranging from the ‘Engineering is done with numbers so an analysis without numbers is only an opinion” and “Your best design efforts will inevitably wind up being useless in the final design so learn to live with the disappointment” to “Three points determine a curve” and “The ability to improve a design occurs primarily at the interfaces, but this is also the prime location for screwing it up” (Akin, 2003). This list specifically allows designers to employ new concepts while maintaining requirements, low cost, and minimal risk; although, despite these regulations, standards, and informal laws, there is little that strictly dictates the specifics of aerospace systems on crew platforms such as this.

Nevertheless, these documents will be used conjointly to develop this comprehensive and holistic crew platform design for multi-crew long-duration deep spaceflight. As Tillman et al. (2007) continue, these documents establish a set of baseline standards that will help ensure humans are healthy, safe, and effectively conduct operations in space. Despite these standards, researchers Lim and Hermann (2012) note that these requirements easily vary from program to program due to crew size, mission duration, and other specific mission and crew factors, while the methods for employing them may also vary from one system or mission to another.

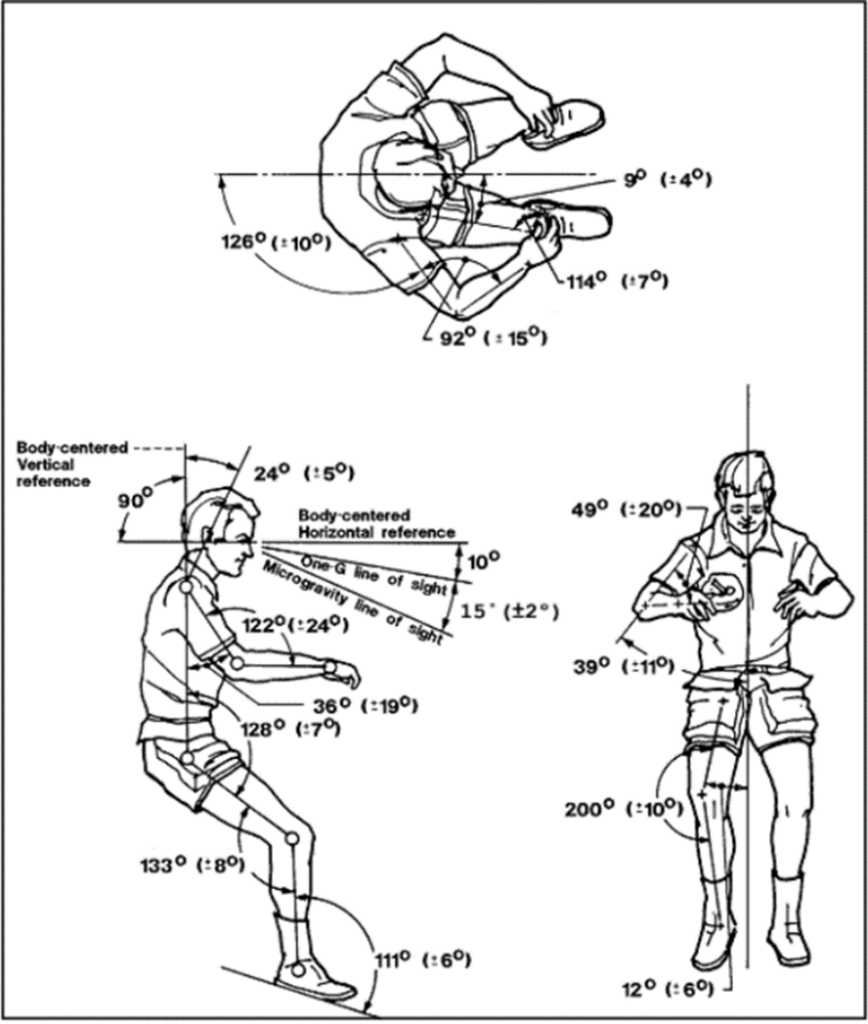

The final key document used throughout the design of a more holistic and human-centric crew platform is the Neutral Body Posture (NBP), which is the postural standard established by NASA that is used in the ergonomic design of aerospace systems, shown below in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Neutral Body Posture (Adolf, 2020).

Spaceflight Stressors

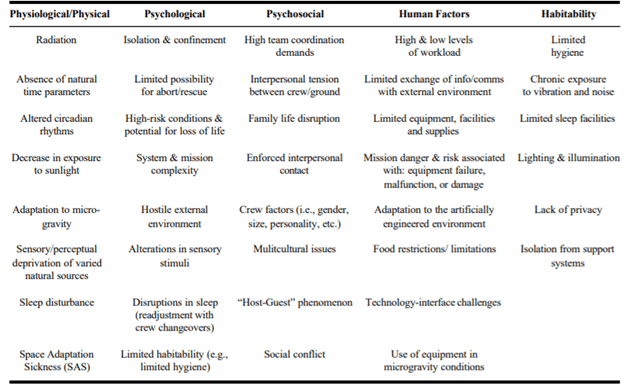

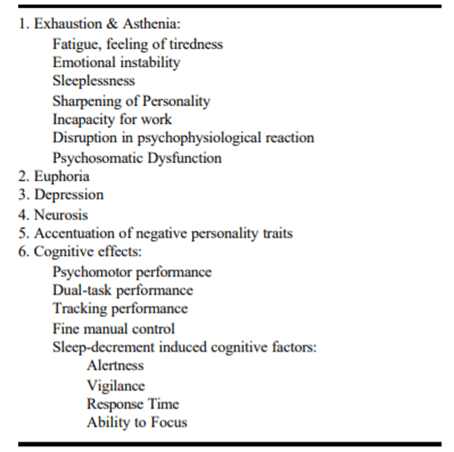

Any discussion of spacecraft operations, like McCann, McCandles, and Hilty (2005) note best, must begin with the fact that human spaceflight is one of the most hazardous and unforgiving activities ever attempted. On these missions, astronauts will experience prolonged exposure to various space-based environmental stressors, including fatigue and circadian disruptions, isolation, confinement, microgravity, and heightened radiation, which all have considerable potential to impact the crewmember’s operational capabilities and overall wellbeing. As Morphew (2001) thoroughly outlines, the spaceflight environment is extremely harsh and characterized by microgravity, solar and galactic cosmic radiation, lack of atmospheric pressure, temperature extremes, noise, vibrations, isolation, confinement, high-speed micrometeorites, and more. As shown below in Figure 3, there is a host of physiological, psychological, and environmental stressors to flight crews of long-duration spaceflight.

Figure 3

Stressors of Long Duration Spaceflight (Morphew, 2001)

In addition to these stressors, astronauts also need to concern themselves with bacteria and potential infection from viruses in space. As noted in “Detecting Bacteria in Space” (2019), space agencies have been trying to reduce the amount of microbial growth in the station since it was first launched in 1998. Despite the strict cleaning and decontamination protocols set in place to maintain a healthy environment where the crewmembers are required to clean and vacuum the station, this environmental stressor still poses a great risk. In fact, the buildup of bacteria inside the cramped quarters can be significant with new bacteria species continually being added, which can be attributed to a range of material including food, lab equipment, live plants, and animals, coupled with the station having no windows to be opened (“Detecting bacteria in space,” 2019). Although the current probes are very good at identifying these bacteria and organisms that we have already seen, they are organism-specific and completely miss many unknown organisms that fall outside the purview of the probe (Larkin, 2003). To mitigate this, researchers from NASA’s National Space Biomedical Research Institute have created a DNA chip to characterize unknown bacteria and viruses in space, as well as help identify biological hazards on Earth (Larkin, 2003). However, like Brion, Gerba, and Silverstein (1994) note, astronauts are likely to be at greater risk for viral infection by consumption of recycled water and air as the length of the mission increases, while these bacteria may behave or evolve differently with the increased explore to radiation and microgravity.

The known impacts of these outlined stressors and this spaceflight environment on human health and performance are numerous and include bone density loss, fluid shifts, effects on cognitive performance, microbial shifts, cardiovascular deconditioning, alterations in gene regulation, and much more (Garrett-Bakelman et al., 2019). Further effects of long-duration spaceflight on human functioning and performance can be seen below in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Effects of Long-Duration Spaceflight on Crew Performance and Functioning (Morphew, 2001).

As researchers Desai, Kangas, and Limoli (2021) assert, exposure to these distinct spaceflight stressors may have an even more profound impact on an astronaut’s ability to perform both simple and complex tasks related to physiological and psychological functioning while on a long-duration mission. To extend this list of stressors, other associated factors related to this crew platform design include motion, clothing, lighting, colors, room size, and display illumination.

As Morphew (2001) outlines, the development of biomedical and physiological countermeasures has been undertaken to begin overcoming these stressors and allow for the sustainment of human presence in flight for increasing periods, as well as to participate in increasingly complex and lengthy missions. However, while many of the above stressors can be alleviated by exercise, pharmacological, and technological interventions, others remain a significant obstacle to maintaining the health of astronauts during long-duration missions (Morphew, 2001). To mitigate the other stressors affecting this crew platform that are not outlined in the above regulatory and industry standards, it is important that the room color and spacing, comfortable clothing, and the inclusion of adjustable lighting, temperatures, display illumination are heavily considered. As Morphew (2001) states best, experience in long-duration spaceflight has demonstrated how extremely capable and adaptable crews are, although it has also demonstrated that if designers and mission executors do not account for these stressors and support the human factor through good design, environmental habitability, and mission support, then the crew’s health, productivity, and overall mission success will suffer.

Anthropometric, Ergonomic, and Biomechanical Considerations

As Cavanagh (2001) accounts, the inclusion of anthropometrics, ergonomics, and biomechanics in aerospace research has been somewhat ignored until the last decade or so, mainly because in the early days of space exploration there was more concern about survivability than comfortability. Later, as Cavanagh (2001) continues, interest shifted from these acute problems to the chronic ones, including an exploration into the ergonomics of the control operations on board and the more biomechanically accessible issues such as bone mineral loss, muscle atrophy, and post-flight alterations in gait and motor control.

Microgravity, specifically, has a great effect on the human body’s dimensions and functionality. As Adolf (2020) describes, body fluid shifts under these conditions where the astronaut will experience spinal decompressions and lengthening, as well as a loss of bone density and muscle mass. In fact, almost all change appears in the spinal column and increases other related dimensions, such as sitting height (buttock-vertex), shoulder height- sitting, eye height, sitting, and all dimensions that include the spine (Adolf, 2020). For example, this will not only increase the overhead reach limits where upward reaches will seem easier, but it will also make downward reaches more difficult since there is no gravity to assist (Adolf, 2020). Thus, for the overall design of this crew platform, how the human body moves and functions in microgravity must be heavily considered.

In addition to microgravity, the location and positioning of the control devices and displays also affect the crewmember’s physiological health. The location and positioning of these displays can negatively affect an individual’s neck, eyes, shoulders, and even wrists, leading to lasting physiological issues, such as fatigue, headaches, and other decrements in performance. The control devices of spacecrafts, due to the limitation of space, tend to be integrated and systematic with excessive display parameters that increase the visual perception and cognitive burden of astronauts (Guo et al., 2017). This strain on the astronauts makes it crucial to consider the anthropometric, ergonomic, and biomechanics of using the control devices and display setups outlined for this crew platform design.

The most important ergonomic consideration for a long-duration spaceflight crew platform is to ensure the astronauts maintain a neutral body posture. As one can imagine, the normal working posture of the body in a microgravity environment differs substantially from that on Earth. The seated posture, as Adolf (2020) notes, is eliminated in this context because it is not natural under the conditions of space and places too much strain on the body. Instead, the neutral body posture is the basic posture used in establishing a microgravity workspace layout or crew platform design (Adolf, 2020), as shown above in Figure 2. Ensuring all crewmembers can function within this baseline posture and their physiological range is crucial for effective and safe long-duration operations and needs to be heavily considered when designing this platform and crew interfaces. This means that the designer will have to choose an orientation of the craft’s systems, the location of all workstations on the platform, as well as design the interfaces to reside within the ranges of this baseline posture. To do this, there will also need to be a careful consideration into how many people are being sent and what individual characteristics each crewmember has.

Generally, the range of personnel considered most likely to be crewmembers in this mission context will be individuals in good health, fully adult in physical development, and an average age of forty years old. Although this group may be either male or female, consisting of about six members from a wide range of ethnic and racial backgrounds, the specific crew population as individuals must be considered in the ultimate design concept. However, as Adolf (2020) adds, it is actually more appropriate to estimate the body dimensions of a future population of the crew for typical long-term space habitat design studies since experience has demonstrated that there is a historical change in average height, arm length, weight, and many other dimensions over time while in space.

Although this population will vary somewhat in size, the equipment and system design must account for this range through three design concepts, being a single-size concept that accommodates all members of the population (i.e. a switch located within the reach limit of the smallest person will allow everyone to reach it), an adjustable-size concept where the design can incorporate adjustment capabilities (i.e. the size of the foot straps can be changed), and a several-size concept that accommodates a full population’s size-range (i.e. the spacesuits come in a small, medium, or large) (Adolf, 2020). Despite these semantics, many of the devices must be individually fitted and custom manufactured for the specific crewmembers. Along with this, other considerations include the critical dimensions of the platform for safety and comfort per the range of crew size to be accommodated, as well as the effects of clothing and personal items on these implementations.

The last mitigation technique is to design for the crewmember’s psychological health. As Zefeld (1986) notes, optimizing the performance activity of man at any workstation requires the consideration of spatial provision both for the motor activity of the skeletal-muscular apparatus and for the optimal course of mental processes that give rise to this motor activity. Ensuring that both the astronaut’s physical and mental health are addressed and optimized through the crew platform design features is essential for successful long-duration spaceflight.

Crew Platform Design Considerations

With these stressors, requirements, and human-centric factors kept in mind, the key design considerations of this crew platform include an open and modular concept consisting of four large interactive LCD control panels with touchscreen graphical user interfaces, coupled with a removable overlapping transparent glass head-up display for training and skill retention purposes, a non-invasive Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) for assistance with control capabilities, and the health monitoring wristband and personal assistant for increased crew support.

This interactive joint-controlled system will be operated entirely through automation, the four large touchscreen control panels, manually by push/pull buttons in case of automation or display failure, through the crewmember’s personal wireless touchscreen tablets, as well as through both the adjustable Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) headset and by voice command. In addition, the systems and interfaces will provide visual, auditory, and haptic feedback to the crewmember outlining the health of both the system and individuals on board. To better understand these systems and their interactions with the crewmembers, the design of this platform’s information display system needs to be addressed

Information Display System Design

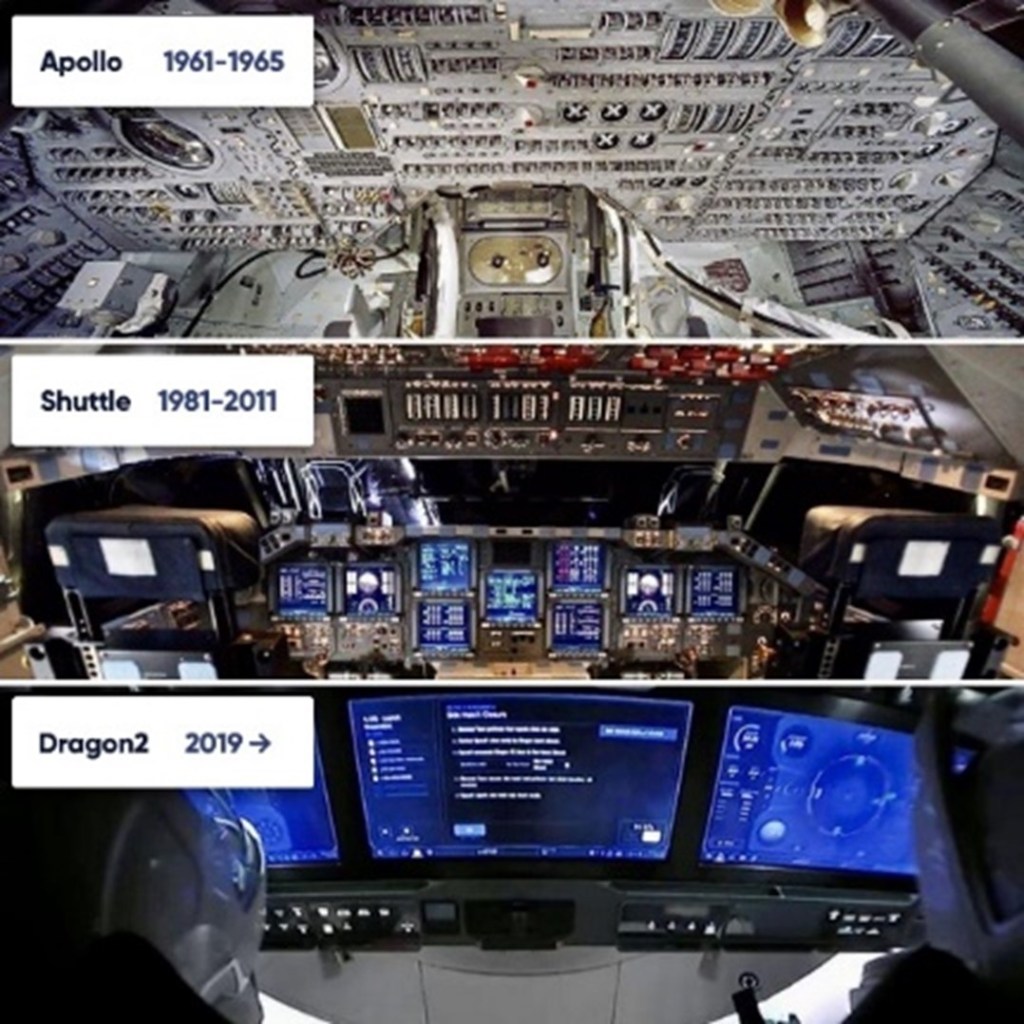

Aerospace applications have developed a considerable need for large information display systems with command control capabilities, which will provide real-time data processing, data acquisition, data transmission, and display generation (Wolfe, 1964). These systems, as Wolfe (1964) states, are needed for planning, assessment, decision-making, and control of increasingly complex and diversified spacecraft systems. As Huemer, Matessa, and McCann (2005) note, previous displays have been data-source-oriented rather than task-oriented, where the displays are poorly organized and highly cluttered with the crew having to navigate through several pages to gather the information needed to complete a task. Instead, these displays should be transparent and consolidated onto a single task-oriented display location of the actual working system to reduce the need for display navigation (Huemer, Matessa, & McCann, 2005). The goal of these displays, as Huemer, Matessa, and McCann (2005) continues, is to improve the correspondence between the presented information and crewmembers’ mental models of the systems architecture and functional mode, therefore enhancing their situational awareness. As shown below in Figure 5, the design and overall structure of control panels for spaceflight have drastically changed over the years and have grown to have a more holistic and human-centered interface.

Figure 5

Spacecraft User Interfaces (Malewica, 2021).

Developing these new and effective systems, like Sherry, Polson, and Feary (2002) describes, lie in the abilities of the designers to understand the mission tasks, provide automation to support the user in executing these tasks, and then address the system’s access, format, and input issues, as well as visual cues and the ability for the user to effectively verify and monitory system activities.

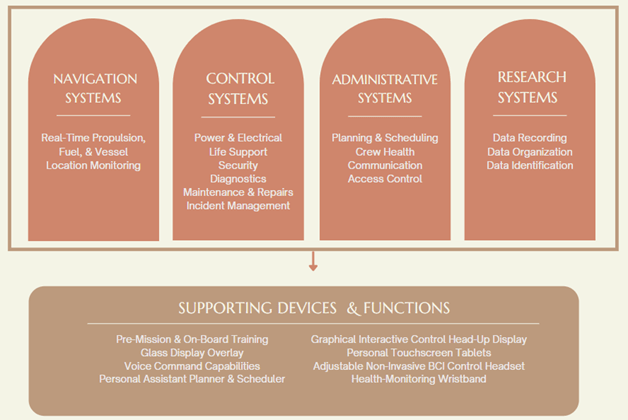

To continue these improvements, the key design features of this crew platform are the large and interactive four-panel HUDs for monitoring and controlling the spacecraft’s functions, as well as the overlaying transparent glass display for skill retention. As shown below in Figure 6, these large touch-panel LCDs will include navigation, control, administrative, and research systems, and have both shared visibility and an audio system throughout the crew platform.

Figure 6

Crew Platform Display Function Outline

As noted above, the information display systems of this crew platform are located in a Head-Up position. Although there may be some wiggle room for the display’s exact location since no gravitational forces are affecting the body, having them be located upward so the crewmembers do not place added strain on their neck or eyes to access the information would be quite beneficial for long-durations. In comparison to a head-down display (HDD), the head-up presentation allows for reduced visual scanning and attention switching while, if designed correctly, reduced display clutter (Wickens, Fadden, Merwin, & Ververs, 1998). As Wilde, Fleischner, and Hannon (2014) continue, the HUD is designed to limit its information content to essential data and to clearly distinguish between levels of significance of display content by symbol color. As Liu and Wen (2004) also mention, users have a much faster response time to urgent or unforeseen events when using a HUD compared to the HDD. As Wilde, Fleischner, and Hannon (2014) also note, HUDs provide an intuitive and accessible reference for trajectory prediction, navigation, and system information, and are generally beneficial to operator performance in rendezvous and docking tasks. These systems also allow astronauts a view outside of the craft, resulting in the platform feeling less confined and isolated.

In addition to these displays, this system will also include a glass HUD that overlaps the main interfaces and allows for the crewmembers to perform training simulations to retain their skills. As McCann and Spirkovska (2005) reinforce, overlaying the control panels with a layer of glass where arbitrary forms of information and symbology, such as ‘virtual’ switches, is presented that will allow the crewmembers to constantly reinforce their spatial representation of control locations and retain their knowledge of the system functions.

Another major design characteristic of this crew platform is the main display’s color, graphical representations, and customization. Since the space environment is devoid of most colors, the crew platform and HUDs’ main parameter in influencing these positive display factors is the symbol-to-background contrast. However, as a general format, the HUD symbols are implemented in bright green, since this color makes symbols discernible in front of both black and white backgrounds, while the color red is reserved for emergency alarms and notifications (Wilde, Fleischner, & Hannon, 2014). To account for operator preferences and long-duration comfortability, this user interface provides the ability to manually switch the non-essential symbols and text in the HUD to other colors such as blue, orange, or purple. As Marsh, Lai, Ogaard, and Ground (n.d.) reinforce, the use of color and color combinations for critical system information should be consistent, as well as both button and font size and type. These dynamic graphical depictions of system components, as well as the system’s colors and text, are incorporated into this display design to provide “at a glance” indications of the operational status and functional mode of the subsystem (Huemer, Matessa, & McCann, 2005). Not only do these mechanisms allow for the direct manipulation and monitoring of real-time system functions, but they also reduce the astronaut’s workload by limiting the amount of memorization needed to complete tasks.

To exploit the full potential of such a system for reducing the operator task load and increasing their situation awareness, special consideration must also be given to the problems of display clutter, symbol design, vehicle motion representation, and cognitive tunneling (Wilde, Fleischner, & Hannon, 2014). As Marsh, Lai, Ogaard, and Ground (n.d.) note, the organization of the information and controls greatly affect the operator’s ability to effectively use the system. Especially in complex systems and scenarios such as long-duration spaceflight, these displays must be navigable, consistent, complete, and relevant while clearly indicating pertinent information.

Information Display System Design Industry Standards

Despite aerospace systems having fundamental design elements to ensure the safety and optimal performance of humans while in space, there are surprisingly very few regulatory requirements for the user interfaces and graphical displays that the astronauts use onboard. As researchers Hopper and Desjardins (1999) outline, vehicle displays often share common requirements across broad spectra of land, air, sea, and space applications. However, there is still little guidance for the display designer about how this information should be displayed, and instead, these requirements merely outline what information needs to be displayed (Harris, 2004). As Harris (2004) continues, even these requirements are difficult to find as these regulations are arranged on a system-by-system basis. Regarding this crew platform’s HUDs, two documents are considered. Although they are not mandatory, the FAA’s preferred options for the display of flight deck instrumentation on electro-optical displays outlined in their 1987 Advisory Circular and the Human Factors Design Guide are used (Harris, 2004), which were both developed as guides for system designers. Another important document applied to this system design is NASA’s Neutral Body Posture (NBP), which is the standard neutral position that the human body assumes in microgravity, as outlined above in Figure 2.

Brain-Computer Interface Design and Industry Standards

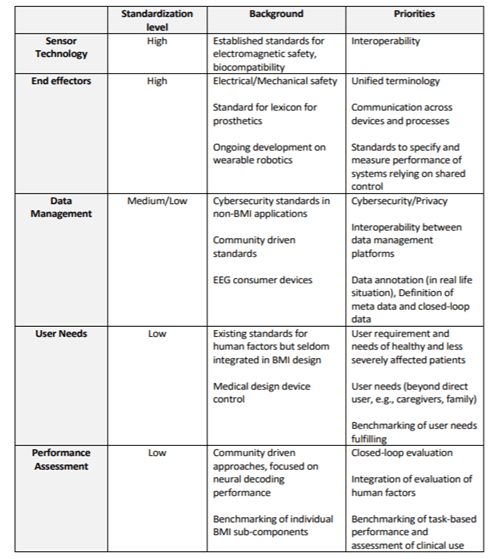

As stated, another central design feature of this crew platform concept is that the control operations can be regulated by a noninvasive Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) headset with interactive voice confirmation capabilities for task executions. As Poli et al. (2013) describe, BCI’s convert signals generated from the brain into control commands for various applications in different areas, like for a control panel’s 2-D pointer, robot control, and augmentative communication technologies. Much of the BCI research to date has focused on topics including data acquisition and signal processing, theoretical foundations including vocabulary and methodology, and conceptual applications or novel prototypes, and while these topics are necessary to ensure this technologies reliability, basic research focusing on the device’s regulations or industry standards is scarce (Ekandem et al., 2012).

To effectively implement BCI technology, their regulations and industry standards need to be considered. As Chavarriaga et al. (2020) thoroughly outline, the level of standardization of BCI-related technologies is quite diverse with aspects of both well-established safety and performance standards, and developments with few regulations. The existing standards, as shown below in Figure 7, typically covers the specific role of that technology such as sensor characteristics, packaging, and physiological safety (Chavarriaga et al., 2020).

Figure 7

Summary of the current BCI standardization and priorities (Chavarriaga et al., 2020).

As shown, there are still a lot of developments needed for safely regulating these complex systems. Specifically, as Chavarriaga et al. (2020) note, there needs to be a thorough investigation into how a BCI integrates and affects the safety and performance of an entire system or person, especially in a long-term context. There also needs to be more exploration into issues of comfort, use limits, and the suitability of this technology with different physical user characteristics.

Despite these drawbacks, the advantages of BCI technology are quite numerous. Not only does this technology provide a non-muscular communication and control channel, but it can also provide biofeedback, detect covert behavior, manage sleep, and assist in diagnosing, treating, and rehabilitating various disorders (Brunner et al., 2011). For space applications, as Poli et al. (2013) outline, these benefits include sending commands with minimum delays and high accuracy, astronauts collaborating in the control of machines such as robots and rovers, gaining machine control in conditions of restricted mobility, and hands-free direct control of cabin instrumentation and equipment. As Ekandem et al. (2012) reinforce, a noninvasive and adjustable BCI headset would promise ease of use, low cost, and untethered mobility for operating controls on this crew platform.

Personal Assistant and Health Monitoring Design and Industry Standards

Other design features that will be used for crewmember support will be the Attentive Remote Interaction and Execution Liaison (ARIEL) agent and a biometric health-monitoring wristband. As McCann, McCandles, and Hilty (2005) describe, ARIEL is a software agent that encodes crewmember-specific knowledge and uses it to customize crew-vehicle interactions. Specifically, one system will be designated for each crewmember, with each agent modeling and recording their location, activity, group role, and availability to help the crewmember in communicating and coordinating within the group (McCann, McCandles, & Hilty, 2005). During the long-duration cruise phases of an extended spaceflight, like McCann, McCandles, and Hilty (2005) continue, crewmembers will typically be spatially distributed throughout the vehicle engaging in any number of activities, such as operating or maintaining the various complex on-board systems and subsystems, sleeping, eating, or attending to personal hygiene. Because of the crewmember’s busyness and the potential for loose or lost group coordination, employing a planning, scheduling, and coordinating assistant for each crewmember would prove quite beneficial for having the most efficient operations and group communication.

These agents will also coincide with a biometric health-monitoring wristband that records and displays the user’s vital signs, ensuring a healthy physiological state for all crewmembers. Wearable Health Devices (WHDs), as Naylor (2021) describes, are an emerging technology designed to continuously monitor and measure a wide range of biometric data in real-time, such as the nine main valuable vital signs including electrocardiogram, heart rate, blood pressure, respiration rate, blood oxygen saturation, blood glucose, skin perspiration, capnography, and body temperature. As researchers McCann, McCandles, and Hilty (2005) outline, having a real-time inference tool that can reliably determine a crewmember’s real-time physiological state and level of functioning is crucial for the continued wellbeing of astronauts on long-duration missions. Similar to an advanced health monitoring system for a machine, this inference tool will not just monitor human performance data feeds in real-time but also accurately classify or diagnose any anomalous behavior and its associated stressor or set of stressors (i.e. fatigue, adaptation, deconditioning, etc.), as well as select an appropriate mitigation strategy (McCann, McCandles, & Hilty, 2005). As Shin, Kang, Jung, and Kim (2021) note, another advantage of this technology are that in addition to these benefits, it has relatively little influence on the surrounding brightness, noise, or the health and comfort of its users. As Naylor (2021) expands, designers of such systems are required to account for the mechanism’s size, its ability to be used on a curved surface, its integration with existing clasps, its ease of assembly and materials used, and the data generation and visualizations while the relationships among band tension, sensor pressure, patient comfort, and signal quality also needs to be considered. By addressing these factors, this technological implementation will not just benefit the individual crewmembers in maintaining their health but will also provide increased chances of an overall successful mission.

Warning, Caution, and Advisory Systems Design Considerations

One of the most important aspects of a new crew platform or a shuttle for space is the warning, caution, and advisory system (WCAs) that alerts the crew to system malfunctions (McCandless, McCann, & Hilty, 2003). Within this crew platform and its four-panel information display system, there will be a display that is devoted entirely to monitoring system functions and displaying critical system alerts and messages, and will include both visual, auditory, and tactile alerts with visual alert information that can be expanded on to assist in diagnosing and fixing the issue. On this central display, only non-normal system conditions and operational events that require crew awareness to support decision making and facilitate the appropriate response should cause an alert, while all alerts presented to the crew must provide the information needed to identify the condition and determine the corrective action (Bahrami, 2010). All flight deck alerts must be prioritized into warning, caution, and advisory categories, with the alerts themselves being prioritized depending on their urgency (Bahrami, 2010). Due to urgency and prioritization requirements, time-critical warnings are first (such as cabin smoke or depressurization) and other warnings are second (such as engine failure), while cautions are third and advisories are last (Bahrami, 2010). The presented information, as Bahrami (2010) continues, must facilitate the crewmember’s ability to identify the alert and determine the appropriate actions.

Furthermore, each critical vessel system will have a dedicated section on the display’s sidebar that will change colors and boldness depending on their status, which provides key “at-a-glance” information about the health of each system (McCandless, McCann, & Hilty, 2003). As researchers Crebolder and Beardsall (2009) reinforce, sidebar alert detection is faster than responding to border alerts within complex environments where it is necessary to perform high-intensity tasks. For time-critical warnings and caution alerts such as incoming space debris or system maintenance, there will be both a unique visual alert and voice tone for each alerting condition. Advisory information, which does not require immediate attention and awareness from the crewmembers, will also be located where the crew is expected to periodically scan for system updates; however, a visual and aural alert will not be used and the information will instead be presented to the crew in a non-interfering manner, such as a banner within the sidebar.

Another key component of this sidebar alerting system will be the fault summary information, containing a text and/or graphic outline describing the malfunctions. This alerting system will not only give a detailed description of the system issue but also automatically produce the correct checklist procedure or synoptic display to respond to the alert when presented, which will be available on the sidebar if the alert is expanded. With this, only root-cause problems and their associated material (i.e. checklists to solve the issue) must be shown in this text region, which as McCandless, McCann, and Hilty (2003) describes, will greatly reduce the workload needed to diagnose an alert. These visual alerts on the display’s sidebar should remain on until it is canceled either manually by the crew or automatically when the alerting condition no longer exists, and after the master visual alert is canceled, the alerting mechanisms should automatically reset to annunciate any subsequent fault condition (Bahrami, 2010). There will also be the inclusion of a “quiet/dark” mode to optimize the deployment of these visual alerts across the displays, which will ensure that only the necessary information will be highlighted until the alert is addressed.

It should also be noted that the colors scheme and attention-getting properties across this platform’s WCAs must be consistent, as should the wording, position, and other attributes for all alerting annunciations and indications. As Bahrami (2010) outlines, visual alert indications must conform to a specific color convention with red for warning alerts, amber or yellow for caution alerts, and any color except red or green for advisory alerts, while green is typically used to indicate “normal” conditions. This color-coding, like McCandless, McCann, and Hilty (2003) note, should facilitate rapid switching of attention between the fault messages and the affected system section, helping the crewmember to navigate the display, prioritize tasks, and diagnose the vehicle more rapidly. There will also be an appropriate use of attention-getting properties, such as flashing, outline boxes, brightness, boldness, and size, so the crewmembers can clearly distinguish between warning, caution, and advisory alerts.

In addition to visual alerts, there will also be auditory and tactile responses to system issues that will warn the crewmembers. To further improve the crew’s ability to diagnose and resolve system malfunctions, unique tones and a natural voice-recognition interface will be incorporated to reduce the need for manual forms of display navigation (McCandless, McCann, & Hilty, 2003). The tones would be pre-set and fixed with varying pitches and volumes depending on the situation, while the crewmembers will have the option of different voices to choose from that will allow them to respond more effectively to any warning phrases or voice alerts that arise. Aural alerts should be prioritized so that only one aural alert is presented at a time, and if more than one aural alert needs to be presented at a time, each alert must be clearly distinguishable and intelligible by the crewmembers; however, all active aural alerts must be interrupted by alerts from higher urgency levels (Bahrami, 2010). Tactile alerts on this crew platform will include a unique vibration pattern on the crewmember’s personal smartwatch, although it will only make the crewmember aware of the issue and not allow them to address it.

WCAs Limitations and Mitigations

As Bahrami (2010) outlines, the purpose of flight crew alerts is to attract the attention of the crewmembers, to inform them of specific non-normal airplane system conditions or certain non-normal operational events that require their awareness, and, in modern alerting systems, to advise them of possible actions to address these conditions. The ability of an alert to accomplish its purpose, as Bahrami (2010) continues, generally depends on the design of the complete alert function, including the sensor and the sensed condition required to trigger an alert and how that information is both processed and displayed. As Bahrami (2010) continues, the crewmembers mustn’t become desensitized to the meaning and importance of these alerts, as this could increase the crew’s processing time, add to their workload, and increase the potential for crew confusion or errors.

As one could imagine, the crew’s desensitization to alerts, which is known as alert fatigue (Ancker et al., 2017), is one of the largest concerns for this crew platform design. According to Ancker et al. (2017), there are two alert fatigue mechanisms, including cognitive overload associated with the amount of work, the complexity of work, and effort distinguishing informative from uninformative alerts, as well as desensitization from repeated exposure to the same alert over time. Essentially, alert fatigue is connected to the complexity of work and the proportion of repeated alerts (Ancker et al., 2017). With this phenomenon increasing along with the growing exposure to alerts, maintaining the crewmember’s situational awareness is crucial.

Because of this, as Bahrami (2010) states, there will need to be alert inhibit functions to prevent the presentation of an alert that is inappropriate or unnecessary for a particular phase of operation. Alert inhibits should be used when an alert could cause a hazard if the crew was distracted by or responded to the alert, when the alert provides unnecessary information or awareness of the vessel’s conditions, or when several consequential alerts may be combined into a single higher-level alert (Bahrami, 2010). Moreover, for as long as the inhibit exists, there will be a clear and unmistakable indication that the crewmember(s) manually inhibited that alert (Bahrami, 2010).

Another way to prevent alert fatigue is by increasing alert specificity and tailoring alerts to crew characteristics, tiering alerts according to the severity and making only the severe alerts interruptive, and by applying human factors principles when designing these systems with the consideration of alert format, content, legibility, and color (“Alert Fatigue,” 2019). Having a redundant backup alerting system would also assist in crewmembers ‘ situational awareness and responsiveness to the alerting system. All of this will assist in ensuring that the crew members maintain their situational awareness and responsiveness to the alerts and are both effectively responding to and interacting with the overall system.

WCAs Design Requirements and Industry Standards

Although there is a bit of leniency in display design, there are many regulations for flight alerting systems to ensure safe and effective operations. Specifically, NASA’s Space Flight Human-System Standard (NASA-STD3001) makes specific recommendations on the use of cues, prompts, and other aids, as well as the frequency of system updates and messages. The use of alerts, including their visual, auditory, and tactile characteristics, are also addressed in this document. Although these specifications were thoughtfully employed in the design considerations above, as Bahrami (2010) advises, it is most crucial to use a consistent philosophy for alerting conditions, urgency and prioritization, and presentation.

Systems Information Management

With such a complex system within a uniquely harsh environment, there is bound to be a plethora of system data and information that must be managed. The management techniques and technologies must not only assist in the sociotechnical system assessing risks, problem-solving, and making decisions but also with assisting the crewmembers in reducing their workload. As Freed et al. (2005) note, an intelligent user interface is required that can combine information from various levels of abstraction and interpret it for the user. Even when operating in a fully autonomous mode, the user should be able to quickly assess the state of the system being controlled as well as the control activities required to achieve the goal state and when problems occur, the user should be able to determine what went wrong, how the problems affect ongoing and planned activities, and whether manual action is required (Freed et al., 2005). In addition to this, as Freed et al. (2005) continue, the interface should provide pertinent information at a fast enough rate such that the user can spot trouble in time and should quickly alert the user when the control system needs help. As researchers McCann and Spirkovska (2005) summarizes best, the central design requirements for these complex interfaces are that they provide an efficient organization of graphical depictions of system components and the systems architecture like valves, tanks, and flow lines, they enable crewmembers to precisely track system changes, and they enable and coordinate a “permissions-based” concept for the human-automation interaction that keeps the crewmembers in close synchronization with the mission operations. Having functional allocation between human and machine authority, responsibilities, and tasks, as well as developing and validating user interfaces to coordinate human and machine activities, is necessary for a successful mission and spacecraft design (McCann, McCandles, & Hilty, 2005). To avoid authority issues, it is crucial to determine a functional allocation between humans and machines that avoids the “out-of-the-loop” issues and capitalizes on the strengths and capabilities of both humans and machines, thereby optimizing the capabilities of the joint system (McCann, McCandles, and Hilty, 2005). As McCann, McCandles, and Hilty (2005) further note, this allocation must strike a balance between the workload reduction that automation inspires with the potential loss of situation awareness that can occur when the human is not providing sufficient oversight of the machine operations or interacting with the systems.

Thus, a key design feature of this crew platform concept is an integrated and interactive planning and scheduling framework where activities are generated and scheduled by a personal agent, with the approval of the crewmembers. As Fukunaga, Rabideau, Chien, and Yan (1997) define, planning is the selection and sequencing of activities such that they achieve one or more goals and satisfy a set of domain constraints while scheduling is an optimization task that selects among alternative plans and assigns resources and times for each activity so that tardiness or disruption is minimized. This automated planning and scheduling technology, as Fukunaga, Rabideau, Chien, and Yan (1997) continues, has great promise in reducing operations costs and increasing the autonomy of aerospace systems, as well as reducing the astronaut’s workload. This reconfigurable, modular automated framework for planning and scheduling applications will not only manage spacecraft operability and timelines including resources, activities, and projects, but it will also assist in science efforts such as planning and data collection, identification, and organization (Fukunaga, Rabideau, Chien, & Yan, 1997). As researchers Padalko, Ermakov, and Temmoeva (2020) note, collecting and analyzing large volumes of data obtained during aerospace research is time-consuming, costly, and often full of repetitive tasks, which have resulted in the need for integrated, human-centric, and automated control systems.

Along with this implementation, an inevitable next step in space design are displays with formal and informal interactive dialogue capabilities between the human and computer where the human can specify new uncertainties, provide sample data, add activities, and adjust the overall system (Fuchs, Girimonte, Izzo, & Neumaier, 2008). This human-machine interaction is not just necessary for the health and safety of the crewmembers on this long-duration spaceflight, but also for maintaining the automation and overall system functions.

To safeguard these human-machine and crewmember interactions and the overall functioning of these systems, and to mitigate the potential for uncertainties to arise and ensure failure tolerance in this design, these systems need to be redundant. Having these backups or fail-safes in this design is essential to improving system performance and ensuring reliability and overall sustainability while in deep space. As McCann, McCandles, and Hilty (2005) outline, much of the engineering complexity of onboard space systems is due to building in operational redundancies so that if a component fails, a backup operational mode exists to restore or maintain full system functionality. For this crew platform concept, double redundancy will be used for essential components such as reaction control hardware or data management units, while single redundancy will be sufficient for non-safety-critical components. By adding these redundancies, the crew can check and crosscheck the system values and functions to continuously determine the health of each software system and the veracity of its navigation and guidance computations (McCann, McCandles, & Hilty, 2005). As Wander and Förstner (2013) add, using cross-strapping redundant hardware makes the spacecraft fully tolerant to almost every single point failure; although, this requires thorough fault identification that determines a faulty unit, flags it accordingly, and employs corrective or mitigative measures. However, as McCann, McCandles, and Hilty (2005) further describe, redundancy requirements do not stop with the software or hardware and need to extend to the crewmembers. To protect against a general breakdown in the data processing system, the crew should have full capability to perform automated functions manually. Ideally, the reverse would also be true where the automation acts as a backup in the event crewmembers cannot contribute. These redundancies are necessary for the optimal design and functioning of this crew platform; however, there will need to be thorough cost-benefit analyses and risk assessments to decide what redundancies are necessary and most cost-efficient for such a trip.

Discussion

This specific crew platform design is developed with a multidisciplinary and human-centric approach, complete with an interactive architecture that considers the physiological, psychological, and environmental aspects of the human being undergoing long-duration space travel. With this, an extremely important aspect in the design of this crew platform is habitability. This is not just a space where these individuals work and accomplish operational tasks for a short duration, but one where they will spend months and even years of their lives operating these systems, making memories, and forming experiences with one another. This habitability, as Zefeld (1986) notes, requires the assurance of motor activity, performance activity, and cognitive activity. Thus, the purpose of this design solution is to not just implement systems that are functional and eases the crewmember’s workload, but those that inspire the health and wellbeing of everyone on board for successful long-duration spaceflight.

Although the space mission environment is defined greatly by mission planners, engineers, and a plethora of environmental, political, temporal, financial, and engineering constraints, many factors cannot be so easily controlled (Morphew, 2001). Despite previous knowledge and the known regulations and industry standards, there are many developments needed for safely implementing and regulating these complex systems. As Chavarriaga et al. (2020) note, there needs to be a thorough investigation into how these systems are integrated and how they affect the safety and performance of an entire system or person, especially in the long-term spaceflight context. It should also be noted that due to the scope of this project, many other potentially useful design factors were not explored such as augmented reality or virtual reality for crew entertainment, health, and skill retention. In addition, there is much more room for elaborating on the general layout of the crew platform, the architectural form and semantics of the entire space vessel, and the specifics of the display interfaces with a thoughtful production of mockups and wireframes.

However, as Zefeld (1986) outlines best, the crew platform and overall spacecraft design are in direct dependence on the specifics of the mission and functions performed by the crew members, the characteristics of the astronauts, the building material of the spacecraft, the duration of the flight, and other such factors. The optimality of a spacecraft design, as Fuchs, Girimonte, Izzo, and Neumaier (2008) also notes, can depend on multiple objectives including the cost or the mass of the spacecraft. This broadness makes simulating all design considerations a critical step to ensuring the safety of the crew and the success of the overall mission. As researchers Nozhenkova, Isaeva, and Vogorovskiy (2016) outline, simulation models can be used and are a crucial aspect of testing complex aerospace systems, allowing for the consideration of structure and methods of interactions between the system elements for finding the optimal functioning features and overall design. As Fukunaga, Chien, Mutz, Sherwood, and Stechert (1997) note, the importance of simulating the spacecraft design to ensure system safety. Therefore, although it may be a promising concept, this design needs to prove its performance, predictability, observability, and reliability.

Conclusion

As shown, several designs and interfaces are key to this platform concept, including the main control panels, tablets, BCI, and the personal assistant and biometric health-monitoring wristband. These described user interfaces will not only assist the crewmembers in maintaining their health and making continuous determinations but also reduces the crewmember’s workload while promoting their situational awareness and skill retention. As McCann and Spirkovska (2005) note, these developments also reduce the real-estate requirements of the physical control panels and allow for both crosschecks and system redundancy.

How the crewmembers interact with this crew platform features and devices, especially in such an unforgiving environment, is crucial for their safety, wellbeing, and overall mission success. Thus, the main goal in this document was to consider technologies and design features that lessen all possible physiological and psychological effects on the crewmembers while ensuring they are fully prepared to respond to adverse and unknown situations. By considering and implementing these human-centric principles, automation, and system features into this crew platform, it is more likely that outer space will not just be a place of survival but one where the human species will thrive.

References

Adolf, J. (2020, August 27). Anthropometry and Biomechanics. NASA. https://msis.jsc.nasa.gov/sections/section03.htm.

Aerospace Industry Standards. NQA. (n.d.). https://www.nqa.com/en-us/certification/sectors/aerospace.

Alert fatigue. Patient Safety Network. (2019, September). from https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer/alert-fatigue.

Ancker, J. S., Edwards, A., Nosal, S., Hauser, D., Mauer, E., & Kaushal, R. (2017). Effects of workload, work complexity, and repeated alerts on alert fatigue in a clinical decision support system. BMC medical informatics and decision making, 17(1), 1-9.

Akin, D. (2003). Akin’s Laws of Spacecraft Design. UMD Space Systems Laboratory.

Bahrami, A. (2010). Advisory Circular: Flight Crew Alerting. AC 25.1322-1.

Bozzano, M., Cimatti, A., Katoen, J. P., Katsaros, P., Mokos, K., Nguyen, V. Y., … & Roveri, M. (2014). Spacecraft early design validation using formal methods. Reliability engineering & system safety, 132, 20-35.

Brunner, P., Bianchi, L., Guger, C., Cincotti, F., & Schalk, G. (2011). Current trends in hardware and software for brain-computer interfaces (BCIs). Journal of neural engineering, 8(2), 025001.

Cavanagh, P. (2001). Biomechanics On the International Space Station: The Past, Present, and Future: The Dyson Lecture. In ISBS-Conference Proceedings Archive.

Chavarriaga, R., CARY, C., Contreras-Vidal, J. L., McKinney, Z., & Bianchi, L. (2021). Standardization of neurotechnology for brain-machine interfacing: state of the art and recommendations. IEEE Open Journal of Engineering in Medicine and Biology, 2, 71-73.

Crébolder, J. M., & Beardsall, J. (2009). Visual alerting in complex command and control environments. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting (Vol. 53, No. 18, pp. 1329-1333). Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.

Desai, R. I., Kangas, B. D., & Limoli, C. L. (2021). Nonhuman primate models in the study of spaceflight stressors: Past contributions and future directions. Life Sciences in Space Research.

Detecting bacteria in space (2019). NewsRX LLC.

Ekandem, J. I., Davis, T. A., Alvarez, I., James, M. T., & Gilbert, J. E. (2012). Evaluating the ergonomics of BCI devices for research and experimentation: Brain-computer interface (BCI) and ergonomics. Ergonomics, 55(5), 592-598.

Freed, M., Bonasso, P., Ingham, M., Kortenkamp, D., Pell, B., & Penix, J. (2005, January). Trusted autonomy for spaceflight systems. In 1st Space Exploration Conference: Continuing the Voyage of Discovery (p. 2521).

Fuchs, M., Girimonte, D., Izzo, D., & Neumaier, A. (2008). Robust and automated space system design. In Robust Intelligent Systems (pp. 251-271). Springer, London.

Fukunaga, A., Chien, S., Mutz, D., Sherwood, R. L., & Stechert, A. D. (1997, July). Automating the process of optimization in spacecraft design. In 1997 IEEE Aerospace Conference (Vol. 4, pp. 411-427). IEEE.

Fukunaga, A., Rabideau, G., Chien, S., & Yan, D. (1997, July). Aspen: A framework for automated planning and scheduling of spacecraft control and operations. In Proc. International Symposium on AI, Robotics and Automation in Space (pp. 181-187).

Garrett-Bakelman, F. E., Darshi, M., Green, S. J., Gur, R. C., Lin, L., Macias, B. R., … & Turek, F. W. (2019). The NASA Twins Study: A multidimensional analysis of a year-long human spaceflight. Science, 364(6436).

Guo, Q., Xue, C., Lin, Y., Niu, Y., & Chen, M. (2017, July). A study for human-machine interface design of spacecraft display & control device based on eye-tracking experiments. In International Conference on Engineering Psychology and Cognitive Ergonomics (pp. 211-221). Springer, Cham.

Han Kim, K., Young, K. S., & Rajulu, S. L. (2019). Neutral Body Posture in Spaceflight. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting (Vol. 63, No. 1, pp. 992-996). Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.

Harris, D. (2004). Human factors for civil flight deck design. Routledge.

Hopper, D. G., & Desjardins, D. D. (1999). Aerospace Display Requirements: Aftermarks and New Vehicles. in Proceedings of the 6th Annual Strategic and Technical Symposium “Vehicular Applications of Displays and Microsensors” (Society for Information Display (S I D) Metropolitan Detroit Chapter, 1999), pp. 59-62.

Huemer, V. A., Matessa, M. P., & McCann, R. S. (2005). Fault management during dynamic spacecraft flight: effects of cockpit display format and workload. In 2005 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics (Vol. 1, pp. 746-753). IEEE.

Internationale, F. A. Human Space Flight Requirements for Crew and Space Flight Participants: Final Rule. Online at http://edocket. access. GPO. gov/2006/pdf/E6-21193. pdf.

Larkin, M. (2003). New technology identifies bacteria in space. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 3(1), 3-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00499-7

Lim, G., & Herrmann, J. W. (2012) NASA-STD-3001, Space Flight Human-System Standard and the Human Integration Design Handbook. Proceedings of the 2012 Industrial and Systems Engineering Research Conference.

Liu, Y. C., & Wen, M. H. (2004). Comparison of head-up display (HUD) vs. head-down display (HDD): driving performance of commercial vehicle operators in Taiwan. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 61(5), 679-697.

Malewicz, M. (2021, June 2). SpaceX: simple, beautiful interfaces are the future. UX Collective. https://uxdesign.cc/simple-beautiful-interfaces-are-the-future-9f77e33af5c4 (Links to an external site.).

Marsh, R., Lai, Y., Ogaard, K., & Ground, A. P. (n.d.) Aerospace Aircraft Display System.

Masi, C. G. (2003). Automation in aerospace–taking the human out of the loop. (automation & robotics). R & d, 45(1), A7.

McCandless, J. W., Hilty, B. R., & McCann, R. S. (2005). New displays for the space shuttle cockpit. Ergonomics in Design, 13(4), 15-20.

McCandless, J. W., McCann, R. S., & Hilty, B. R. (2003). Upgrades to the caution and warning system of the space shuttle. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting (Vol. 47, No. 1, pp. 16-20). Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.

McCann, R., McCandless, J., & Hilty, B. (2005). Automating vehicle operations in next-generation Spacecraft: Human factors issues. In Space 2005 (p. 6751).

McCann, R. S., & Spirkovska, L. (2005, November). Human factors of integrated systems health management on next-generation spacecraft. In First International Forum on Integrated System Health Engineering and Management in Aerospace, Napa, CA (pp. 1-18).

Morphew, E. (2001). Psychological and human factors in long-duration spaceflight. McGill Journal of Medicine, 6(1).

NASA Space Flight Human-System Standard Volume 2: Human Factors, Habitability, and Environmental Health1–196 (2015). Washington, DC; National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Naylor, T. A. (2021). Exploration of Constant-Force Wristbands for a Wearable Health Device.

Nozhenkova, L. F., Isaeva, O. S., & Vogorovskiy, R. V. (2016, April). Automation of spacecraft onboard equipment testing. In International Conference on Advanced Material Science and Environmental Engineering (ISSN 2352-5401) (pp. 215-217).

Padalko, S. N., Ermakov, A. A., & Temmoeva, F. M. (2020). Methodology for evaluating the effectiveness of integrated automation in the aerospace industry. INCAS Bulletin, 12(S), 135-140. https://doi.org/10.13111/2066-8201.2020.12.S.12

Poli, R., Cinel, C., Matran-Fernandez, A., Sepulveda, F., & Stoica, A. (2013, March). Towards cooperative brain-computer interfaces for space navigation. In Proceedings of the 2013 international conference on Intelligent user interfaces (pp. 149-160).

Reed, C. (n.d.). Aerospace Sector Information. EPA. https://www.epa.gov/smartsectors/aerospace-sector-information.

Sherry, L., Polson, P., & Feary, M. (2002). Designing user-interfaces for the cockpit: Five common design errors and how to avoid them (No. 2002-01-2968). SAE Technical Paper.

Shin, S., Kang, M., Jung, J., & Kim, Y. T. (2021). Development of Miniaturized Wearable Wristband Type Surface EMG Measurement System for Biometric Authentication. Electronics, 10(8), 923.

Tillman, B., Pickett, L., Russo, D., Stroud, K., Connolly, J., & Foley, T. (2007). NASA Space Flight Human System Standards.

Truszkowski, W., Hallock, H., Rouff, C., Karlin, J., Rash, J., Hinchey, M., & Sterritt, R. (2009). Autonomous and autonomic systems: with applications to NASA intelligent spacecraft operations and exploration systems. Springer Science & Business Media.

Wander, A., & Förstner, R. (2013). Innovative fault detection, isolation and recovery strategies on-board spacecraft: state of the art and research challenges. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Luft-und Raumfahrt-Lilienthal-Oberth eV.

Wickens, C. D., Fadden, S., Merwin, D., & Ververs, P. M. (1998). Cognitive factors in aviation display design. 1 E32/1-E32/8 vol.1. https://doi.org/10.1109/DASC.1998.741568 (Links to an external site.)

Wilde, M., Fleischner, A., & Hannon, S. C. (2014). Utility of head-up displays for teleoperated rendezvous and docking. Journal of Aerospace Information Systems, 11(5), 280-299. https://doi.org/10.2514/1.I010104 (Links to an external site.)

Williams, R., Wilcutt, T., Roe. R. (2015) NASA Space Flight Human-System Standard Volume 2: Human Factors, Habitability, and Environmental Health1–196. Washington, DC; National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Wolfe, C. E. (1964). Information system displays for aerospace surveillance applications. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace, 2(2), 204-210. https://doi.org/10.1109/TA.1964.4319590

Zefeld, V. V. (1986). Spacecraft Architecture.

Originally created by Samantha Colangelo to fulfill requirements for Embry Riddle Aeronautical University’s Master of Science program in Human Factors. August, 2021.