Through a human-centered research study, this paper explores the general public’s perception of spaceflight safety. Understanding these viewpoints is crucial for the continued development of space capabilities and increasing the support and involvement of people in spaceflight endeavors, as well as establishing a more stable and sustainable human presence in space with the development and fulfillment of new industry positions. Especially with the fluctuating involvement from the government and private companies, gaining this insight is necessary to ease public ignorance and reluctance to participate in aerospace industry activities. This issue is investigated through an anonymous survey, allowing for a deeper understanding of the general viewpoints on spaceflight safety. Previous literature and industry reports that pertain to aerospace operations and incidents provided the secondary data for analysis. This data is assessed thoroughly through a comparative analysis between the public perceptions of spaceflight risks and the actual risk of spaceflight according to accident and incident data. The results of this study support the hypothesis that a statistical significance exists between the public perceptions of spaceflight risk and the actual risk of spaceflight according to accident and incident data. In all, this indicates that the differences between the public perceptions of spaceflight risk and the real-world industry risks are not likely to occur randomly or by chance. As noted in other research, a common explanation for this result is that the public’s skepticism of human spaceflight safety has fueled the conduction and success of these inherently dangerous endeavors.

Keywords: spaceflight, risk, safety, perception, viewpoints, aerospace industry

List of Tables

Table 1

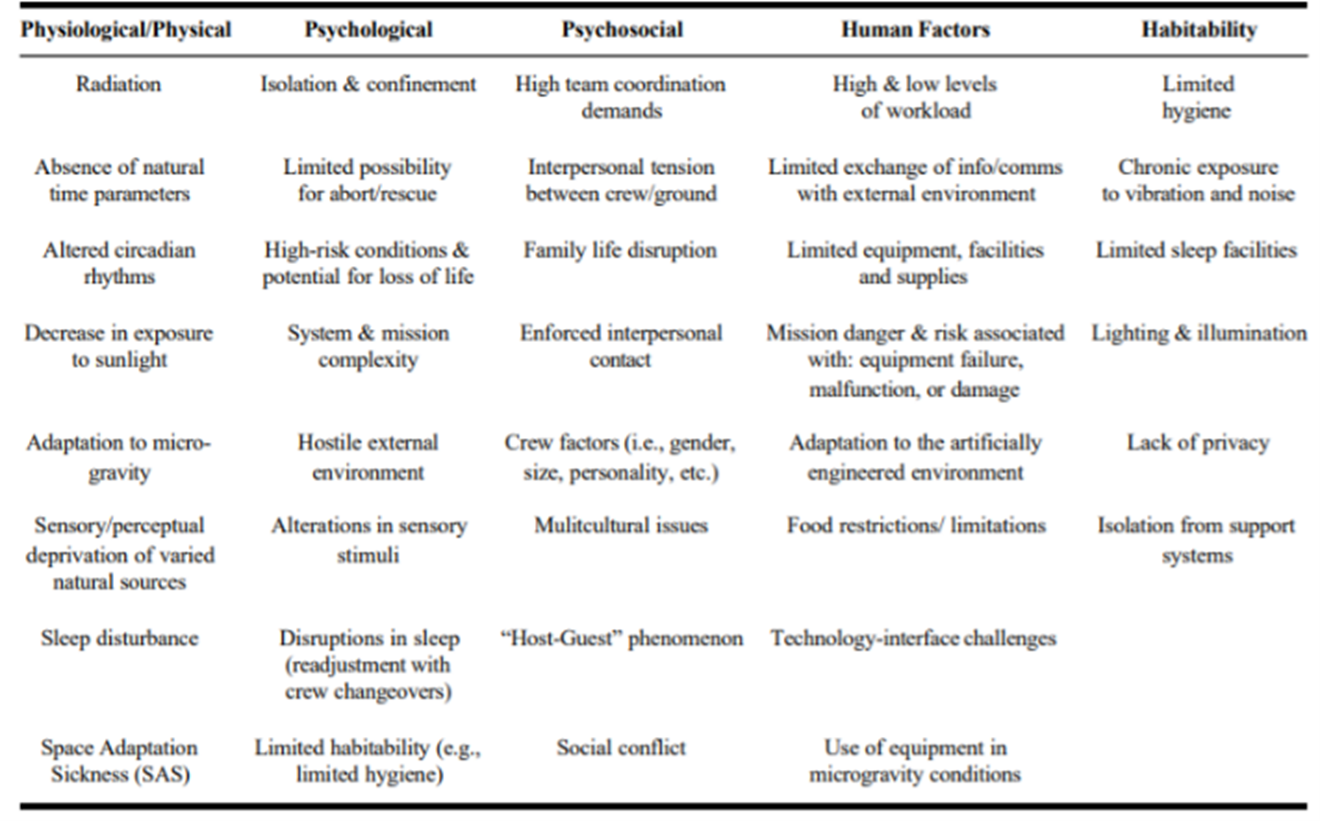

Stressors of Long Duration Spaceflight (Morphew, 2001).

Table 2

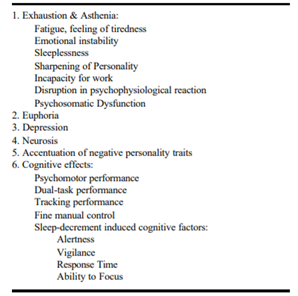

Effects of Long-Duration Spaceflight on Crew Performance and Functioning (Morphew, 2001).

Table 3

Chi-Square Distribution of the Public Perceptions of Spaceflight Safety and the Aerospace Industry’s True Accident/Incident Rates.

| Survey Questions | Correct Answer | Observed | Expected | Residual | Diff^2 | Diff^2 / Expected |

| “How many total fatal accidents/incidents do you think has occurred during spaceflight? | 15 to 24 | 6 | 92 | -86 | 7396 | 80.39 |

| “How many total non-fatal accidents/incidents do you think have occurred during spaceflight?” | 25+ | 38 | 92 | -54 | 2916 | 31.7 |

| “How many total accidents/incidents do you think have occurred while training for spaceflight?” | 25+ | 41 | 92 | -51 | 2601 | 28.27 |

| Survey Questions | Critical Value | P-Value | x^2 value | Result |

| “How many total fatal accidents/incidents do you think have occurred during spaceflight? | 113.15 | < 0.01 | 265.6 | Reject The Null Hypothesis |

| “How many total non-fatal accidents/incidents do you think have occurred during spaceflight?” | 113.15 | < 0.01 | 184.4 | Reject The Null Hypothesis |

| “How many total accidents/incidents do you think have occurred while training for spaceflight?” | 113.15 | < 0.01 | 177.7 | Reject The Null Hypothesis |

Table 4

A Correlation Matrix of Seven Survey Questions and Participant Demographics (n=90).

| Participant Demographics | |||

| Survey Questions | Age | Gender | Political Viewpoint (PV) |

| “How likely would you be to go to space, if given a chance?” | 0.17 | 0.21* | -0.06 |

| “How do you feel about the safety of human spaceflight?” | 0.14 | 0.1 | -0.06 |

| “I think spaceflight is safe for people in short durations (<1 month).” | 0.21* | 0.19 | -0.03 |

| “I think spaceflight is safe for people in long durations (>1 month).” | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.01 |

| “How many total fatalities do you think have occurred during spaceflight?” | 0.11 | 0.14 | -0.19 |

| “How many non-fatal accident/incidents do you think have occurred during spaceflight?” | -0.1 | -0.07 | 0.01 |

| “How many total accidents/incidents do you think have occurred while training for spaceflight?” | -0.09 | -0.07 | -0.12 |

List of Figures

Figure 1

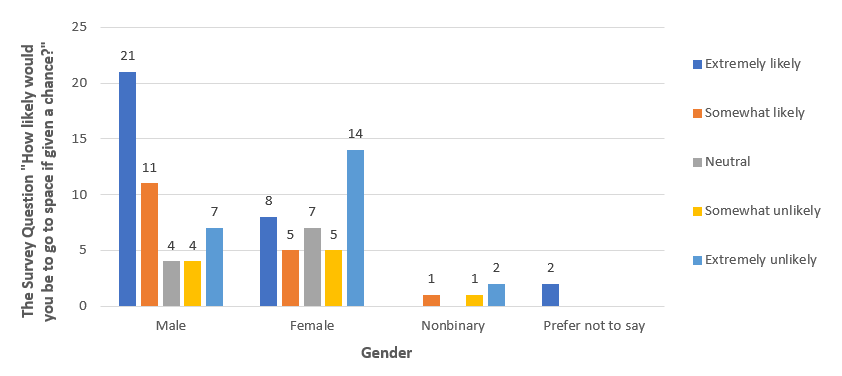

Gender VS. The Survey Question “How likely would you be to go to space, if given a chance?”

Figure 2

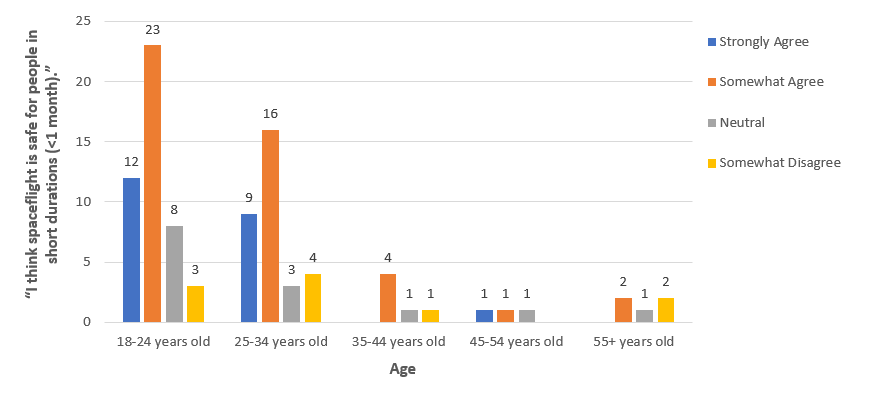

Age VS. The Survey Question “I think spaceflight is safe for people in short durations (<1 month).”

Figure 3

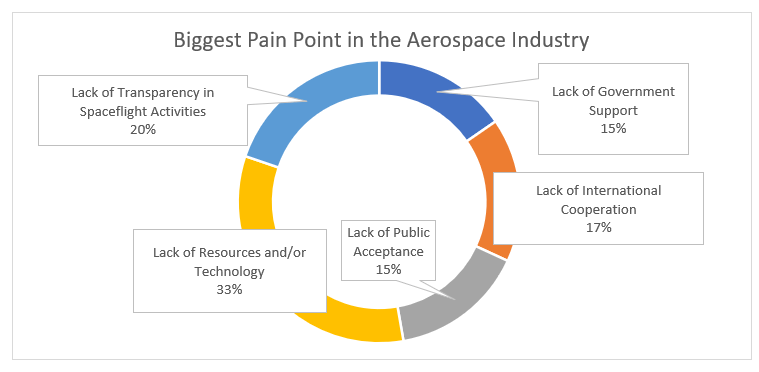

Participant Responses to “Of the following, which do you think is the biggest pain point in the aerospace industry?”

Figure 4

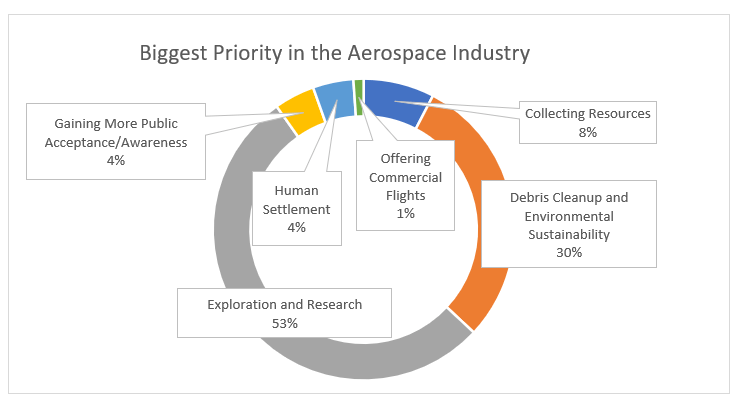

Participant Responses to “Of the following, which do you think is the biggest priority in the aerospace industry?”

Figure 5

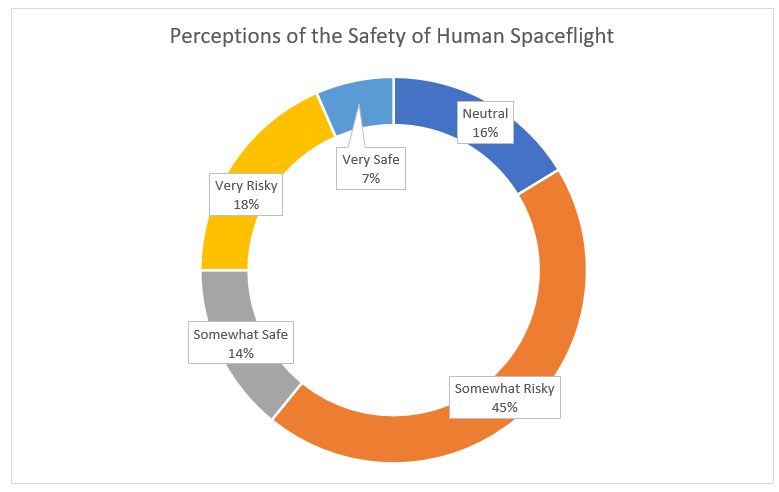

Participant Responses to “How do you feel about the safety of human spaceflight?”

Public Perceptions of Spaceflight

The decade following World War 2 brought a sea of changes in the perceptions of spaceflight, as most individuals went from being skeptics to quick acceptance of it as a near-term reality (Launius, 2017). Convincing the public that spaceflight was possible was one of the most critical debates of the 1950s, and without it, the aggressive exploration programs of the 1960s would never have been approved (Launius, 2017). The public must have an appropriate vision and confidence in the attainability of these goals; however, a fundamental reality since the beginning of spaceflight has been the public lacking understanding and support of aerospace activities (Launius, 2017). The quest for gaining a popular appeal of spaceflight, as shown throughout the years, remains quite elusive. As Launius (2017) notes, only a small base of supporters advanced most aerospace activities, which have been challenged by only a small group of opponents and sustained by those who have accepted a status quo in space exploration. Meanwhile, as Launius (2017) found, the spaceflight support trends over time suggest that the public generally does not seem to know or care very much, does not think about these issues in much detail, and is disengaged from the topic. This general dismissal of spaceflight makes their societal impact and overall influence on spaceflight quite problematic (Bimm, 2018).

Thus, the overarching goal of this research is to investigate the general public perceptions of spaceflight safety compared to the actual industry data. Understanding these public viewpoints is essential for continuing industry development with the fulfillment of new positions, inspiring more support and involvement from the public, improving our spaceflight and overall technological capabilities, and creating a more stable and sustainable human presence in space. As such, the investigated research question this study explores is as follows: Is there a difference between the public perception of spaceflight risk and the actual risk of spaceflight?

H1: There is a statistical significance between the public perception of spaceflight risk and the actual risk of spaceflight.

HO: There is no statistical significance between the public perception of spaceflight risk and the actual risk of spaceflight.

As Launius (2017) notes best, understanding the public’s support for human spaceflight agendas must occur for developing environments more conducive to establishing aggressive space programs, which is necessary for space colonization and the overall continuation of the human species. It is also essential for creating stability throughout the industry, despite the governments and private companies fluctuating involvement over the years. Overall, conducting this research to improve understanding of what the public perceives regarding the risks of spaceflight is necessary for providing transparent aerospace industry activities, easing the ignorance about spaceflight risks, and inspiring increased public participation and support of these endeavors.

Limitations, Delimitations, and Assumptions

Despite the usefulness of this research, this study contains several limitations, including a stark absence of funding, having limited time to complete the study, not being able to infer causality from the correlational analysis, and the sample not being generalized enough to represent the entire human population. There was also a notable lack of consistent open-source aerospace data on accidents and incidents with a lack of consistent terminology when reporting such incidents, as there is no standardized or required reporting system available. Other limitations are results that are restricted by the reliability of the statistical tests used to assess the collected data, and that the current social trends and the locality of the randomly selected participants in the Florida area may affect the results of this study.

To address these limitations while ensuring that this research is both manageable and timely, several delimitations were established, including the age of the participants needing to be 18 years or older, all participants needing to reside in the United States of America (US), and the study taking a total of seven weeks to complete. Another delimitation of this study is the multiple-choice and Likert scale responses that were employed so more people would be willing to complete the survey. Finally, several assumptions of this research exist, including the notion that spaceflight is a dangerous activity with harsh effects on the human body over long periods, that the participants of this study are interested in the aerospace industry or spaceflight, and that all participants of this survey answered individually with truth and honesty.

List of Acronyms

FAA Federal Aviation Administration

IRB Internal Review Board

US United States of America

NASA National Aeronautical Space Association

Review of the Relevant Literature

While the spaceflight community may rightfully deem these travelers and space pioneers the avant-garde of progress, along with these ventures comes undeniable risk (Langston, 2018). While human spaceflight is recognized as being inherently dangerous with relatively new activities encompassing a large scale of uncertainty, is not that unlike the past where sailors frequently charted unknown waters (Langston, 2018). As Langston (2018) argues, human spaceflight and the effort to reach space expands the peripheries of our knowledge of the physical world, transcending the limits of human imagination, capability, and control.

Thus, to assess the potential and actual harm of spaceflight, there needs to be a good understanding of what risk is in this context and the associated stressors of space. As Langston (2018) defines, the term “risk” generally refers to an undesirable event, the cause of an undesirable event, or a lack of knowledge of the unknown. The categorization of risk levels, priorities, and variety associated with spaceflight differ based on the type of launch and reentry, vehicle design and flight technology, trajectory, and duration of the spaceflight (Langston, 2018). In analyzing the main risks in human spaceflight operations on the national level, concerns include identifying the likelihood of physiological and psychological harm to humans and innocent third parties like the public, as well as the impact on local and national economies, legal systems, and the environment (Langston, 2018).

As Morphew (2001) thoroughly outlines, the harsh spaceflight environment is characterized by several threats, such as microgravity, solar and galactic cosmic radiation, a lack of atmospheric pressure, temperature extremes, high-speed micrometeorites, and increases in noise, vibrations, isolation, and confinement. There is also risk that lies in the myriad of uncertainties about the safety and control of new launch and spaceflight technologies, unknown space hazards, and undetermined impacts on an average human’s health, as well as unregulated training and medical requirements for those participating (Langston, 2018). As shown, Table 1 outlines other known spaceflight threats and stressors.

In addition to these stressors, astronauts also need to concern themselves with bacteria and potential infection from viruses in space. This list of spaceflight stressors is also extended to the crew platform design and includes motion, clothing, lighting, colors, room size, and display illumination. As researchers Weiss, Leveson, Lundqvist, Farid, & Stringfellow (2001) discovered through the many similarities and parallels of different aerospace accidents, other risk factors include low fidelity simulation and test environments, having to collect and use safety-related information with inadequate specifications and instructions, not understanding the technology and automation along with limited communication channels and poor information flow, as well as exhibiting overconfidence and complacency with the assumption that risk decreases over time.

As researchers Desai, Kangas, and Limoli (2021) assert, exposure to these spaceflight stressors may have an even more profound impact on an astronaut’s ability to perform both simple and complex tasks related to physiological and psychological functioning while on a long-duration mission. The known effects of these outlined stressors and this spaceflight environment on human health and performance are numerous and include effects on cognitive performance, bone density loss, fluid and microbial shifts, cardiovascular deconditioning, alterations in gene regulation, and much more (Garrett-Bakelman et al., 2019). Further effects of long-duration spaceflight on human functioning and performance are in Table 2. As Cates (2021) notes, these risks and associated effects are amplified by the duration of time spent under the known harsh environmental conditions, as well as there being no plans or attendant capabilities in place for the timely rescue of a crew from a disabled spacecraft while in space.

As Morphew (2001) outlines, the development of biomedical and physiological countermeasures has begun overcoming these stressors and is now allowing for the sustainment of human presence in space for increasing periods with more complex missions. Careful medical screenings and selection processes of participants, routine evaluations, and customized preflight training are just a few techniques used for mitigating these spaceflight risks (Langston, 2018). However, while exercise, pharmacological, and technological interventions can alleviate many of the above stressors, others remain a significant obstacle to maintaining the health of individuals during these missions (Morphew, 2001), especially for long durations.

To further mitigate these risks, many regulations and industry standards need to be met, with both formal and informal contributors. As noted by Reed (n.d.), the agencies that are primarily responsible for regulating the aerospace sector are the Department of Defense (DOD), Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). For example, the FAA passed a regulation in 2006 regarding commercial spaceflight with specific requirements for crew and spaceflight participant training and consent (Internationale, n.d.), while the EPA has specific standards for the emissions and air pollutants produced by aerospace facilities (Reed, n.d.). Other organizations also provide certifications if particular industry standards are met, with the most common being the Nuclear Quality Assurance (NQA). In fact, most organizations operating in the aerospace industry are required to register to one of their specific compliance standards, such as AS9100, AS9110, and AS9120, which covers a wide range of areas, including product safety, configuration management, raw material testing, manufacturing, post-delivery support, and more (“Aerospace Industry Standards,”n.d.).

Despite this progress, as Langston (2018) notes, the commercial space transportation industry’s recent developments are shifting the burden of risk from government and government-sponsored missions that can be meticulously controlled to private commercial entities and individuals with more freedom to conduct unsafe operations. Although the US has perceived space as a place for knowledge and progress since 1957, as well as a new frontier for science, defense, security, and international cooperation, spaceflight and exploration have drastically wavered in national public opinion polls and served as a consistent tool for political and diplomatic agendas (Langston, 2018). Opening access to space to members of the public not only significantly raises novel concerns for increased risk awareness and risk management among voluntary participants (Langston, 2018), but also highlights the need for evaluating and clarifying societal perspectives on issues of standardization, transparency, and risks of spaceflight.

Methodology

The overarching aim of this study, taking approximately seven weeks to complete, is to report on differences between the general public’s perceptions of spaceflight risk and the actual risk of spaceflight. The employed methodology in this research is a mixed-methods approach that contains qualitative and quantitative data, providing for a more complete means to investigate the stated issue. Through a triangulation design, this research entails the collection and analysis of both qualitative data from various databases and quantitative data from both random survey participants and secondary sources.

To investigate this significance between the public perceptions of spaceflight risk and the actual risk of spaceflight, a primary research study is conducted with a survey which was first presented to the Internal Review Board (IRB) at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University to gain research approval. With this approval, the participants were recruited with a simple random sampling technique through the professional online platform LinkedIn and locally in the Orlando/Daytona, Florida area with a target sample size of 100 individuals. The only participants recruited for this study were eighteen years of age or older and those who reside in the US while people living outside of the US were excluded from the study due to their lessened exposure to aerospace industry activities. These randomly recruited participants were asked to complete a voluntary and anonymous questionnaire through GoogleForms, which is an online and mobile device survey platform. This questionnaire only took approximately ten minutes to complete and consists of twenty-five multiple-choice questions and Likert scale responses, with nine demographic-oriented and sixteen related to aerospace, and one optional open-ended question for any closing thoughts or feedback. All survey responses from outside of the US, from individuals under 18 years old, and from those who disagreed with the terms of the research study were effectively deleted and not included in the analysis of the data or the results of this study, while the usable and voluntary data was collected, organized, and analyzed on Microsoft Excel software. All survey data collected throughout this study is both anonymous and confidential, is only used for this research study, and will be effectively deleted at the end of December 2021.

To compare this data on the public perceptions of spaceflight, secondary data on aerospace accidents and incidents were obtained from previous literature, the FAA’s reporting systems, NASA reports, and various aerospace organization reports. This primary and secondary data were collected, organized, and analyzed on Microsoft Excel software, with both data being synthesized through descriptive and inferential statistics and nonparametric tests. Specifically, Chi-Square tests were used to show whether the observed proportions of spaceflight risk perceptions differ from the industry risk proportions. Correlation tests were also applied to see if there is a relationship between different variables such as gender and spaceflight risk perceptions or age and willingness to go to space. In all, this will allow for more insight into the relationship between the general public’s perceptions of spaceflight risk and the actual risk of spaceflight.

Results

As noted, chi-square tests were conducted to assess whether the public perceptions of spaceflight risk are similar to the actual risks of spaceflight according to aerospace accident and incident data. It was theorized that a statistical significance exists between the public perceptions of spaceflight and the true spaceflight risks according to the industry’s accident and incident data. In addition, several correlational tests were used to determine the relationship between varying demographic factors and aerospace industry perceptions. Of the 106 participants who voluntarily completed this study, 14 (13.2%) participants were excluded for not meeting the study criteria of this research, as they did not live in the US. This resulted in a final total of 92 participants for this research study.

Although all collected data was usable, only the participant’s Age (M=18-24 years old at 50%), Gender (M=Male at 51%) and Political Viewpoint (M=Very Liberal at 24%) were assessed, as well as the responses to the survey questions “How do you feel about the safety of human spaceflight?” (M= ,SD=), “I think spaceflight is safe for people in short durations (<1 month).”, “I think spaceflight is safe for people in long durations (>1 month).”, “How many fatal accidents/incidents do you think has occurred during spaceflight?”, “How many non-fatal accident/incidents do you think has occurred during spaceflight?”, “How many total accidents/incidents (both fatal and non-fatal) do you think have occurred while training for spaceflight?”, “How likely would you be to go to space, if given a chance?”, “Of the following, which do you think is the biggest pain point in the aerospace industry?” and “Of the following, which do you think should be the biggest priority in the aerospace industry?”. The other demographic questions, including the participants home location, ethnicity, religion, education, employment status, their service-member status, and the survey questions “What is your affiliation to the Aerospace Industry?”, “How interested are you in spaceflight?”, “Which do you think is safer, in terms of accidents/incident rates?”, “I support the current human spaceflight agenda.” “I think it is unsafe to have private companies send people to space.”, “I support commercial spaceflight.”, and “I am confident in the current spaceflight capabilities.” were excluded from the data analysis as they did not adequately assist in assessing the stated research hypothesis.

For the ease of data assessment, several demographic variables were coded. These codes were applied to the participant’s Age (“18-24 years old” as 1, “25-34 years old” as 2, “35-44 years old” as 3, “45-54 years old” as 4, and “55+ years old” as 5), Gender (“Male” as 1, “Female” as 2, “Nonbinary” as 3, “Prefer Not to Say” as 4), and Political Viewpoint (“Very Liberal” as 1, “Somewhat Liberal” as 2, “Neutral” as 3, “Somewhat Conservative” as 4, “Very Conservative” as 5, “Independent” as 6, “Other” as 7, as “Prefer Not to Say” as 8). Several survey questions were also coded, such as “How likely would you be to go to space, if given a chance?” (“Extremely likely” as 1, to “Extremely unlikely” as 5), “How do you feel about the safety of human spaceflight?” (“Very Safe” as 1. to “Very Risky” as 5), “I think spaceflight is safe for people in short durations (<1 month)” and “I think spaceflight is safe for people in long durations (>1 months)” (“Strongly Agree” as 1, to “Strongly Disagree” as 5), as well as “How many fatal accidents/incidents do you think has occurred during spaceflight?”, “How many non-fatal accident/incidents do you think have occurred during spaceflight?” and “How many total accidents/incidents (both fatal and non-fatal) do you think have occurred while training for spaceflight?” (“0-4” as 1, “5-9” as 2, “10-14” as 3, “15-24” as 4, “25+” as 5).

Chi-Square

As shown in Table 3, several chi-square tests were completed between the public perceptions of spaceflight risk and the actual spaceflight industry risk, exploring whether the observed proportions of spaceflight risk perceptions differ from the industry risk proportions.

According to the industry data, there were a total of nineteen fatal spaceflight accidents/incidents, thirty-two non-fatal spaceflight accidents/incidents, and over forty spaceflight training accidents/incidents that have occurred. This industry information was then compared to the collected data on the public perceptions of spaceflight risk.

The first chi-square tests of independence showed a significant difference between the public perceptions of spaceflight risk, in terms of fatal accidents/incidents, X2(90, N=92) = 265.6, p < .01. The chi-square tests of independence also showed a significant difference between the public perceptions of spaceflight risk, in terms of non-fatal accidents/incidents, X2(90, N=92) = 184.4, p < .01. Finally, the chi-square tests of independence showed a significant difference between the public perceptions of spaceflight risk, in terms of training accidents/incidents, X2(90, N=92) = 177.7, p < .01. Since the calculated chi-square values of 265.6, 184.4, and 177.7 are all greater than the critical chi-square value of 113.15, there is strong evidence to reject the null hypothesis of ‘no statistical significance.’ Thus, it is concluded that there is a statistical significance between the public perceptions of spaceflight risk, including fatal, non-fatal, and training incidents, and the proven risk of spaceflight according to the aerospace industry data.

Correlations

Several bivariate correlations were conducted between survey questions on the perceptions of spaceflight and participant demographics, as outlined in Table 4, and as shown, only two results were found to be statistically significant. A Pearson correlation coefficient was computed to assess the linear relationship between Gender and the survey question “How likely would you be to go to space if given a chance?”. There was a positive correlation between these two variables, r(90) = [0.21], p = [0.04], indicating that gender differences likely impact a person’s willingness to go to space. A Pearson correlation coefficient was also computed to assess the linear relationship between Age and the survey question “I think spaceflight is safe for people in short durations (<1 month).” There was a positive correlation between the two variables, r(90) = [0.21], p = [0.05], indicating that a person’s age is likely related to how safe they perceive short-duration spaceflight. While the other correlations were not significant relative to the standard alpha level of .05, several of the p-values were less than .10, which is displayed in Table 4.

Other Results

Although statistical tests were not used to assess these relationships, it was discovered that the public perceives the biggest pain point in the aerospace industry to be a lack of resources and/or technology (33%), in comparison to a lack of transparency in spaceflight activities (20%), a lack of government support (15%), a lack of public acceptance (15%), or a lack of international cooperation (17%). Moreover, the public perceives the biggest priority of the aerospace industry as conducting exploration and research (53%), compared to debris cleanup and environmental sustainability (30%), collecting resources (8%), establishing human settlement (4%), gaining more public acceptance/awareness (4%), and offering commercial flights (1%). These relationships can be seen in Figures 3 and 4 and are a testament to the public perceptions of the aerospace industry’s largest obstacles and where their support lies for future endeavors.

Discussion of Results

As outlined above, the purpose of this research is to investigate the public perceptions of spaceflight risk in comparison to the actual risk of spaceflight according to the industry data. The results of this study support the stated hypothesis that there is a statistical significance between the general public perceptions of spaceflight risk and the actual risk of spaceflight according to accident and incident data. This indicates that the differences between the public perceptions of spaceflight risk and the true industry risks are not likely to occur randomly or by chance. It is determined, with confidence, that this relationship between public perceptions and industry trends is true and likely to occur in the real world. As supported in other research, one explanation for this result is that public skepticism regarding the safety of human spaceflight has fueled the conduction and success of these inherently dangerous endeavors, as well as a lack of transparency regarding industry safety standards and occurring incidents.

As it can also be inferred from the participant’s voluntary responses about their additional thoughts on spaceflight and the aerospace industry, the public generally seems to be skeptical about the important contributions and impact that the aerospace industry and spaceflight have made and will continue to make. As one anonymous participant wrote, “I appreciate the real scientific research going on but nowadays, with these private companies getting involved, it seems more like a waste of resources, time, and money.” In addition, another participant states that “there are too many people here on Earth that need care, and it seems quite wasteful and unempathetic to be sending people into space instead.” With this, a final anonymous participant notes that “spaceflight is a waste of resources and instead, that money should be spent on saving our planet and people from suffering.” Amongst these voluntary responses, there were also several notes of spaceflight not benefiting the average citizen, the development of a “billionaire space race,” a general distaste for space tourism, and wanting more transparency in aerospace activities. In all, these results coincide with the claims of previous researchers, such as Launius (2017) who found that the public’s support for spaceflight wavers while many individuals’ hold seemingly contradictory attitudes, mainly being that most are in favor of human exploration and development of space and view it as at least somewhat important but also believe that money could be better spent on other programs. Despite this ignorance, the aerospace industry and human spaceflight have both developed many technologies and contributed to the discovery of many answers to real-world problems, acting as a beam of inspiration for innovation and collaboration that has propelled general knowledge and understanding of the world.

In addition to this discovery, the results of this research also led to a positive correlational relationship between the public’s gender and their willingness to go to space, as well as the public’s age and their perception of short-duration spaceflight safety. As Morrongiello and Rennie (1998) note, this may be due to the male gender and people younger in age being more willing to take risks. With this, it is vital to note that people may perceive danger and risk differently, where one group may consider some conditions unnecessarily hazardous while another may see them as adequately safe and necessary (Weiss, Leveson, Lundqvist, Farid, & Stringfellow, 2001). Risk can be seen as both fact-laden and objective yet value-laden and subjective (Langston, 2018), leading to the difference between unacceptable and acceptable risk. In effect, this implies that there is legal and moral permissibility of voluntary personal risk-taking action in the face of rational cognitive decision-making capability and informed consent (Langston, 2018). Thus, despite the risks that occur in human spaceflight, there will be participants that aim to pioneer the spaceflight frontier.

Conclusion and Recommendations

As it was well noted, the public perceptions of spaceflight have changed drastically over the years and have still shown to be quite hypocritical. Although the public generally supports spaceflight, there is a notable lack of support for financing such endeavors with a stark disapproval of space tourism. Nevertheless, there are many personal and financial reasons to support spaceflight. As Launius (2017) notes, the five main rationales for spaceflight include scientific discovery and technological development, national security and military applications, economic competitiveness and commercial applications, national prestige and geopolitics, and human destiny and the continued survival of the species.

Despite these reasons and the various innovations that spaceflight brings, there is still much ignorance and misunderstandings that exist about the safety of human spaceflight.

As the results of this study show, those who identify themselves as male generally display more of a willingness to go to space while people younger in age generally perceive that short-duration spaceflight is safe. Moreover, there is a statistical difference between the public’s perception of spaceflight safety and the real safety of spaceflight according to accident and incident data, indicating a reason behind the public’s perceptions, such as spaceflight endeavors lacking transparency and media coverage.

As it was also thoroughly noted, spaceflight is an inherently dangerous activity yet there are extensive safety measures and other precautions set in place to mitigate these risks. Nevertheless, as displayed above, accidents and incidents have not only happened but are bound to continue happening along with the progression and increased frequency of human spaceflight. However, as Langston (2018) notes, major risk alone does not lead to a valid justification to abandon progress and development of a field or activity where their benefits and value are both achievable and desirable. Thus, it is recommended that human spaceflight continues moving forward with exploration and research, while the people’s positive perception and increased participation will soon follow with more media coverage and transparency.

With this, further research is recommended to develop a more generalized and applicable study on the perceptions of spaceflight safety. Future studies should consider obtaining a larger and more diverse pool of participants. The development and implication of a standard safety reporting system for aerospace accidents and incidents also needs to be developed. As Christensen (2017) suggests, creating an industry-wide safety reporting system that is standardized, mandatory, and focuses on operational hazards, incidents, and close calls are a proven and effective way to give the public transparency on the activities and safety of spaceflight while also filling in any gaps left by accident investigations and other voluntary information-gathering systems. By standardizing the aerospace system’s checks-and-balances while also making it more transparent for the public, individuals will have more access to important safety information regarding spaceflight while also inspiring more public interest and willingness to participate in the exciting new frontier of human spaceflight.

References

Aerospace Industry Standards. NQA. (n.d.). https://www.nqa.com/en-us/certification/sectors/aerospace.

Bimm, J. (2018). Historical Studies in the Societal Impact of Spaceflight ed. by Steven J. Dick. Technology and Culture, 59(1), 183-185.

Cates, G. (2021). The in-space rescue capability gap. Journal of Space Safety Engineering, 8(3), 202-210.

Christensen, I. (2017). The elements of a commercial human spaceflight safety reporting system. Acta Astronautica, 139, 228-232.

Commercial Space Data. Federal Aviation Administration. (2021, April 21). Retrieved October 14, 2021, from https://www.faa.gov/data_research/commercial_space_data/.

Desai, R. I., Kangas, B. D., & Limoli, C. L. (2021). Nonhuman primate models in the study of spaceflight stressors: Past contributions and future directions. Life Sciences in Space Research.

Garrett-Bakelman, F. E., Darshi, M., Green, S. J., Gur, R. C., Lin, L., Macias, B. R., … & Turek, F. W. (2019). The NASA Twins Study: A multidimensional analysis of a year-long human spaceflight. Science, 364(6436).

Internationale, F. A. Human Space Flight Requirements for Crew and Space Flight Participants: Final Rule. Online at http://edocket. access. GPO. gov/2006/pdf/E6-21193. pdf.

Langston, S. M. (2016). Space travel: risk, ethics, and governance in commercial human spaceflight. New Space, 4(2), 83-97.

Launius, R. D. (2017). NASA’s Quest for Human Spaceflight Popular Appeal. Social Science Quarterly, 98(4), 1216-1232.

Morphew, E. (2001). Psychological and human factors in long-duration spaceflight. McGill Journal of Medicine, 6(1).

Morrongiello, B. A., & Rennie, H. (1998). Why do boys engage in more risk-taking than girls? The role of attributions, beliefs, and risk appraisals. Journal of pediatric psychology, 23(1), 33-43.

Reed, C. (n.d.). Aerospace Sector Information. EPA. https://www.epa.gov/smartsectors/aerospace-sector-information.

SpaceFund Reality Rating Database. SpaceFund. (2021, September). Retrieved October 14, 2021, from https://spacefund.com/launch-database/.

Weiss, K. A., Leveson, N., Lundqvist, K., Farid, N., & Stringfellow, M. (2001, October). An analysis of causation in aerospace accidents. In 20th DASC. 20th Digital Avionics Systems Conference (Cat. No. 01CH37219) (Vol. 1, pp. 4A3-1). IEEE.

Originally created by Samantha Colangelo to fulfill requirements for Embry Riddle Aeronautical University’s Master of Science program in Human Factors. Dec, 2021.